Don’t make assumptions, but communicate with other vessels to get their intentions clear. The Nautical Institute gives this warning in its latest Mars Report in which two vessels collided after poor communication.

The Nautical Institute gathers reports of maritime accidents and near-misses. It then publishes these so-called Mars Reports (anonymously) to prevent other accidents from happening. A summary of this incident:

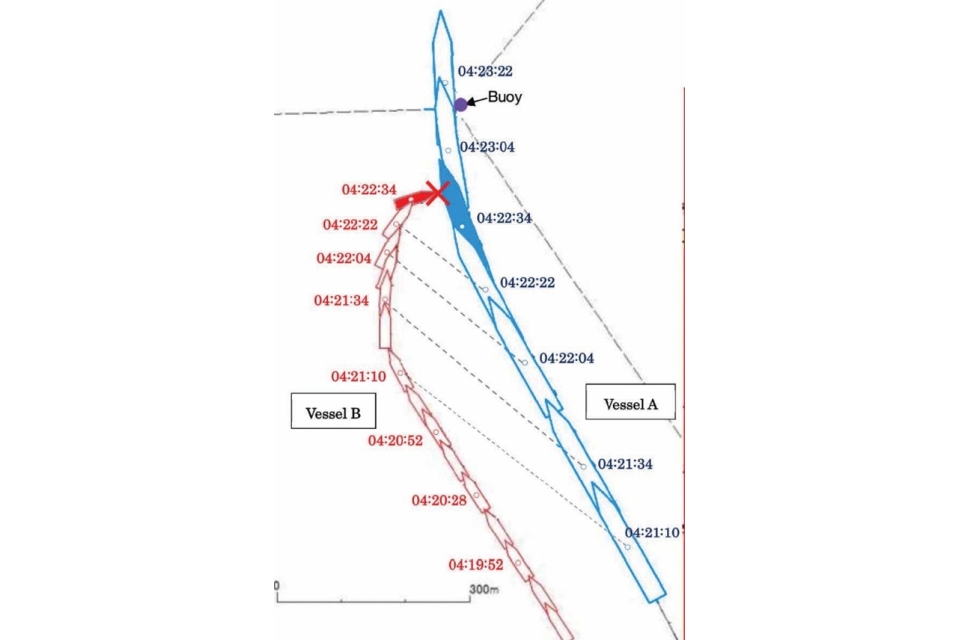

A vessel was making way at about 13 knots, gaining slowly on Vessel B, which was making about 10 knots. The pilot of Vessel A observed Vessel B cross their bow from starboard to port about 0.5 nm ahead. Based on this action, the pilot assumed the vessel was headed for the North exit of the Traffic Separation Scheme (TSS).

Up to this point there had been no VHF communication between the two vessels. Vessel A continued to gain on Vessel B, and it appeared they would pass Vessel B on their port side at a distance of about 200 metres.

Meanwhile, on Vessel B, the lone watch keeper was contacted by the local Vessel Traffic Services (VTS) on VHF. VTS inquired if they were headed to “K” anchorage. The officer of the watch (OOW), although unsure of the exact anchorage, responded in the affirmative.

Also read: VIDEO: Two Royal Navy minehunters collide in Bahrain

The VTS then informed the OOW that in order to make “K” anchorage, they were required to navigate the Traffic Separation Scheme (TSS) on their starboard side. The OOW was surprised, but took the VTS advice as an order. He knew he had to act quickly to enter the TSS, so he informed VTS he was coming to starboard. He knew there was a vessel astern, but without verifying, he assumed it was still some way behind.

The local VTS immediately called Vessel A on VHF and informed the bridge team that Vessel B was destined for an anchorage and that the vessel would take the appropriate TSS to starboard.

At about the same time, the pilot of Vessel A saw Vessel B begin to turn sharply to starboard, which meant that this vessel would cut in front his vessel. He attempted to call Vessel B on VHF but there was no response. He ordered the main engine be put to stop, while the master simultaneously ordered hard to starboard.

At the same time, the OOW of Vessel A blew a long blast on the whistle. Despite all this, a collision was now unavoidable and Vessel B collided with the port side of Vessel A. The starboard bow of Vessel A then struck the navigation buoy that had been close to starboard.

Also read: DSB after water taxi incident: Nieuwe Maas shipping needs more direction

Advice from The Nautical Institute

- Assumptions made by both vessel operators on the actions or position of the other vessel contributed to this accident. Keep your situational awareness honed sharp and communicate with other vessel operators to augment understanding and shared mental models.

- When passing another vessel close by, as in this case about 200m, it may be advisable to have a mutual understanding of the manoeuvre.

Also read: Nautical Institute: ‘Confirm other vessel’s movements instead of making assumptions’

Mars Reports

This accident was covered in the Mars Reports, originally published as Mars 202354, that are part of Report Number 374. A selection of the Mars Reports are also published in the SWZ|Maritime magazine. The Nautical Institute compiles these reports to help prevent maritime accidents. That is why they are also published (in full) on SWZ|Maritime’s website.

More reports are needed to keep the scheme interesting and informative. All reports are read only by the Mars coordinator and are treated in the strictest confidence. To submit a report, please use the Mars report form.

Also read: Assumptions and poor communication lead to vessel collision