An engine crew member recently died during piston replacement. The Nautical Institute discusses the incident in its latest Mars Report and warns to always consult the engine manufacturer’s instruction manual, to conduct a proper risk assessment and to communicate in the vessel’s working language throughout the operation.

The Nautical Institute gathers reports of maritime accidents and near-misses. It then publishes these so-called Mars Reports (anonymously) to prevent other accidents from happening. A summary of this incident:

While at anchor, the engine crew were overhauling a main engine piston. The removal of the piston and stuffing box and the overhaul of the piston were completed without incident.

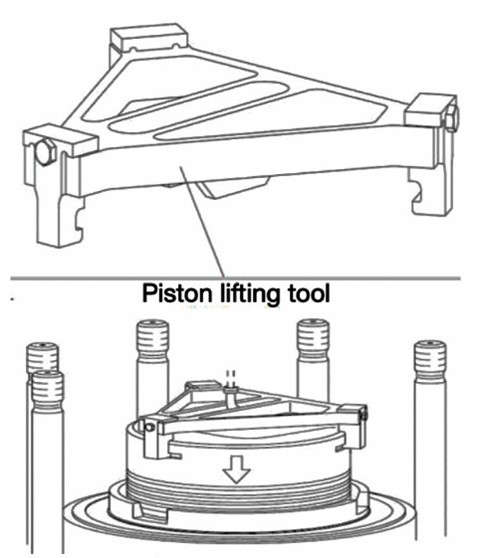

The task had been started in the morning, and in the late afternoon, the crew commenced the re-installation process. This last but critical phase of the overhaul would take about an hour, and included using the piston lifting tool. The lifting tool has two stationary claws and one adjustable claw. The claws sit in the piston lifting grooves on the top of the piston.

An engineer was in charge of lowering the piston using the engine room crane. He was stationed at the upper platform near the cylinder head, along with two assisting oilers. Another engineer was in charge of placing the stuffing box into position, and was inside the crankcase along with the technician and another oiler. The chief engineer was standing outside the crankcase at the lower platform supervising the entire operation.

The two engineers engaged in the work each had a portable VHF radio and they communicated to each other in a language not understood by the chief engineer. Although he was supervising the operation, he himself did not have a VHF radio.

It took about an hour to stow the stuffing box. Once it was tightened in position, the chief engineer instructed the crew to clear all the tools, clean the surfaces and exit the crankcase. Both the engineer and the technician exited the crankcase but the oiler remained inside to clean up the area.

Soon after, the chief engineer instructed an engineer to turn the engine using the turning gear. The other engineer dropped the piston lifting tool. A loud noise was heard; the piston had dropped inside the crankcase. The oiler who had remained inside the crankcase was found unresponsive in the sump tank of the main engine. Emergency procedures were taken but the oiler was declared deceased before his arrival at the hospital.

Investigation findings

The investigation subsequently found, among other things, that:

- The existing risk assessment for this job indicated that crew should take the engine manufacturer’s instruction manual into account while planning the operation. However, in this case the manual was not discussed beforehand and several steps mentioned by the manufacturer were not followed by the crew members during the operation.

- The chief engineer was the supervisor of the operation. However, he did not have a portable VHF radio with him while the task was being carried out. Furthermore, the communication between the two other engineers was in a language not understood by the chief engineer.

Also read: Pilots speaking in local language contributes to vessel hitting breakwater

Advice from The Nautical Institute

- Before carrying out any high-risk operation, such as overhauling and maintenance of the main engine, the manufacturer’s instructions must be discussed and incorporated in the planning of the operation.

- A thorough review of the risk assessments for any high-risk operation must be carried out to identify the hazards and risks associated with every stage of the operation. Appropriate safeguards to eliminate those risks should be put in place.

- Effective communication should be established while carrying out any operation on board. The supervisor of the operation and all involved crew members should be equipped with the appropriate communication devices and communicate in the vessel’s working language throughout the operation.

Also read: Language problems in inland navigation result in more collisions

Mars Reports

This accident was covered in the Mars Reports, originally published as Mars 202148, that are part of Report Number 348. A selection of this Report will also be published in SWZ|Maritime’s November 2021 issue. The Nautical Institute compiles these reports to help prevent maritime accidents. That is why they are also published on SWZ|Maritime’s website.

More reports are needed to keep the scheme interesting and informative. All reports are read only by the Mars coordinator and are treated in the strictest confidence. To submit a report, please use the Mars report form.