A container vessel left port despite heavy fog. The pilot did not share his departure plan with the crew on the bridge. A loss of spatial orientation subsequently led to an allision with a bridge support. An accident that could have been prevented, according to the Nautical Institute.

The Nautical Institute gathers reports of maritime accidents and near-misses. It then publishes these so-called Mars Reports (anonymously) to prevent other accidents from happening. A summary of this incident:

In the early morning hours, a pilot had embarked on a berthed container vessel and was tuning one of the radars prior to departure. He was not satisfied with the results and told the master that, due to the degraded visibility and the poor radar performance, the departure would probably be delayed. He continued to tune the radar with the assistance of the vessel’s master and officer of the watch (OOW). He inquired via VHF radio to both harbour traffic control and other vessels as to the visibility further out in the harbour. From all reports it was very low at about 0.25 nm.

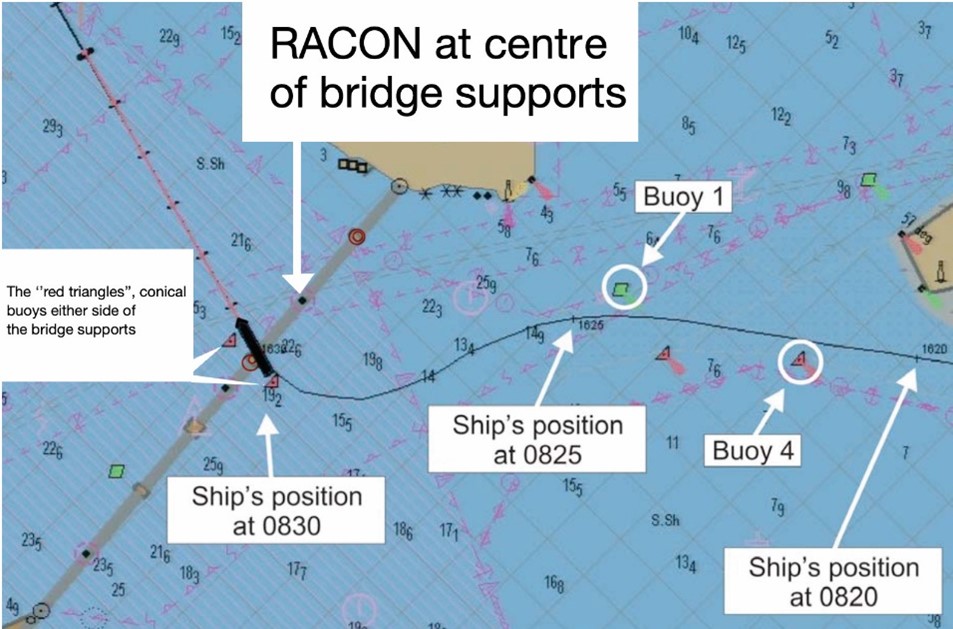

The pilot’s plan to exit the harbour was to use parallel indexing to pass under the bridge and between two of the bridge supports. This was the main shipping channel and the supports were about 670 metres apart, a large gap that was not technically difficult to navigate and marked at mid-section with a radar beacon (RACON).

However, the pilot did not inform the bridge team of his parallel index specifications. Neither did he request that his outbound courses, and specifically the course through the bridge supports, be put on the vessel’s electronic chart. The crew had indicated an outbound course on the paper chart, but the pilot did not appear to have validated this. Neither the Master nor the OOW inquired about the pilot’s navigation plan.

At the point of departure, with visibility still very poor, the master commented ‘The fog is so heavy’. The pilot seemed satisfied with the radar, and his response to the master’s comment was: ‘Single up if you want…’. The master agreed and departure was started. A tug was used to assist the stern away from the berth and then assigned to follow with slack line from the stern fairlead. By 08:06 the vessel was underway. At one point, the vessel’s speed was increased from slow to half ahead at the pilot’s request, giving a speed near 10 knots against a flood tidal current of about one knot.

Also read: Tug order mix-up leads to allision and shore crane collapse

A turn to port was initiated using 10 degrees of port rudder. The vessel soon reached the Variable Range Marker (VRM) ring set at the distance for the parallel index course through the bridge supports. But the pilot seemed to think the radar image of the bridge was distorted, so he turned to the electronic chart. Looking at the screen, he asked the master what the red triangles on the electronic chart represented. The master responded ‘This is on the bridge’. In fact, the red triangles were simply a representation of the two red conical buoys either side of the bridge support, a fact with which the pilot should have been familiar. Meanwhile, the helm was still 10 degrees to port and the helmsman reminded the pilot of this fact. The pilot acknowledged the reminder and, some forty seconds later, asked for midships.

Shortly afterwards, the pilot ordered 10 degrees starboard rudder, then 20, and asked for full ahead. According to the Voyage Data Recorder (VDR) capture of the ship’s radar display at this moment, the ship’s heading was 241° (almost parallel with the bridge) and its course over ground was 255°.

About this time, when the vessel was 0.3 nm from the bridge, a port VTS operator was concerned that the vessel was out of position to make an approach under the bridge. He called the pilot, addressing him by his pilot designator name, “Romeo” instead of the vessel’s name, as was the practice in this port. When the VTS call came, the pilot asked the helmsman to ease to 10° starboard. Once the conversation with VTS was finished, some 25 seconds later, the pilot requested starboard 20° helm once again. Pointing to a place on the electronic chart, the pilot asked the bridge crew: ‘This is the centre of the bridge, right?’ The master responded yes, and soon afterward the pilot requested hard starboard.

Also read: Fatigue and weak bridge practices contribute to expensive allision

Over the next two minutes, the pilot gave rudder orders of hard starboard, mid-ships, starboard 20°, and hard starboard. At 08:29, the crew posted at the bow reported the bridge column close to port. About 10 seconds later, the pilot ordered the rudder midships and then hard port rudder. An allision was now inevitable and the pilot wanted to reduce the swing of the stern towards the bridge support.

The forward port side of the vessel struck the corner of the fendering system at the base of the bridge support at 08:30. The bridge support was unaffected due to the fendering and cement pier skirt but the vessel suffered a large gash. Fuel tanks were punctured, causing pollution. The vessel was subsequently brought to anchorage to allow time to assess the situation.

Advise from The Nautical Institute

- A shared plan where everyone on the bridge is working from the same basis means there is a chance of catching and correcting an error, if it happens.

- In this case, the master had some reservations about the departure, as his comment to the pilot testifies (‘the fog is so heavy’). But he did not question the pilot’s impetus to leave. If you are in charge, take charge.

Also read: Ask, challenge and do your own navigating

Mars editor’s note

The official investigation found, among others, that the pilot suffered degraded cognitive performance due to the number of medications he was taking. This would have probably affected his ability to interpret data, thus degrading his ability to safely pilot the ship under the prevailing conditions. While this may be possible, it is also possible that complacency and thick fog combined into a formidable trap.

A loss of spatial orientation, such as that experienced by aviators who neglect their instruments, is certainly a possibility even without degraded cognitive performance.

But, irrespective of the immediate cause, single point failure was a major contributor to this accident. Had the pilot’s plan been shared with the bridge team, especially the parallel index specifications – and had the pilot’s departure courses been applied to the electronic chart – the chances of the vessel hitting the bridge support would have been much smaller. Hence lesson learned number one above. Better yet, had the departure been postponed until better visibility, the accident would surely have been avoided. Lesson learned number two.

Mars Reports

This accident was covered in the Mars Reports, originally published as Mars 202153, that are part of Report Number 349. A selection of this Report will also be published in SWZ|Maritime’s December 2021 issue. The Nautical Institute compiles these reports to help prevent maritime accidents. That is why they are also published on SWZ|Maritime’s website.

More reports are needed to keep the scheme interesting and informative. All reports are read only by the Mars coordinator and are treated in the strictest confidence. To submit a report, please use the Mars report form.