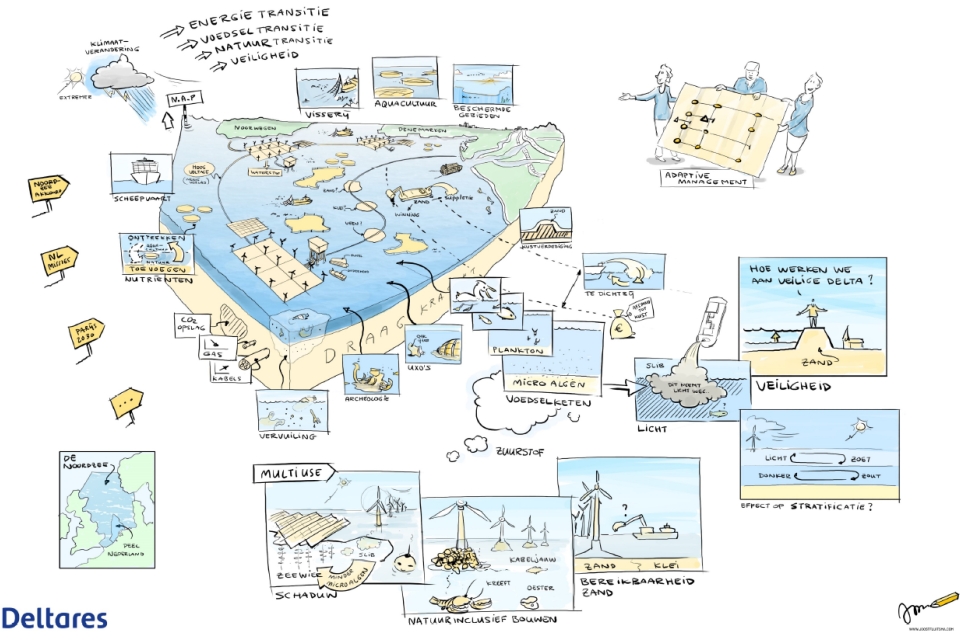

The North Sea looks pretty large when crossing the dunes or when travelling to the UK. However, it is likely not all ambitions the countries around it have can be realised. A very complex balancing of a multitude of interests is required. All this in a highly vulnerable, competitive, legally challenging and (inter)national safety and security context.

This week, SWZ|Maritime’s December 2021 issue comes out. With the North Sea facing ever more uses that each take up space, bringing the different interests in balance is becoming a necessity. That is why our December issue features a special on spatial planning in the North Sea. The article below was written by our editor Johan de Jong of MARIN.

The North Sea, and not just the Dutch part of it, is a well-known place to most of our readers mainly due to their shipping or oil and gas background. Yet, not so well known to the many others who live behind the ever higher dikes. An awareness is growing that our overcrowded country not only needs more living space, but also space to enable our energy transition, extend our agriculture and collect building materials, while proceeding with the mining of fossils, fishing and recreating and continuing to give a safe and efficient passage to a (merchant) fleet growing in size and number and potentially becoming autonomous.

And of course all North Sea ecosystems need to be preserved, our World Heritage – the Wadden Sea – needs to be safeguarded against pollution and last but not least, human life at sea needs to be kept safe.

Also read: Rapid changes in the North Sea require long-term roadmap

The assessment framework

Prior to introducing an overview of all stakeholders in more detail and their interests within the North Sea, it is good to see what is really at stake and needs consideration. Next to the practical policies on the spatial use of the sea, a framework is required, which addresses the governing aspects of a sustainable sea to backup these policies. Look at it as an integral “formal sustainability assessment” (FSuA) framework that goes beyond a project related MER (environmental impact assessment) procedure. The latter is often not able to address the whole picture and/or has to deal with a limited (national) policy framework and missing criteria.

What should be the axes of this framework? By its nature and first of all, the sea is an ecosystem that needs conservation. A lesson we learned the hard way onshore over the past decades (already with noticeable effects on the seas) and this mistake is not to be repeated at sea.

The current monitoring campaigns on the status of the ecosystems are limited in their prevention capabilities as they are looking back (monitoring) and only observe currently known relevant parameters. Ecosystems are not about biodiversity alone, but include basic physical processes like (coastal) morphology and habitat changes caused by the new users.

Next are legal issues. Using sea space and exploitation of resources seems well organised since we have our exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and other jurisdictional defined (smaller) zones. However, the current developments at sea within the wider context of the “Mare Liberum” (The Free Sea) require new international agreement and harmonisation with our immediate neighbours in the first place. Effects on almost any of the stakeholders’ interests will transfer to neighbouring seas and activities. Fishing is the obvious example, free passage of merchant vessels a second important one.

Last but not least are the growing importance of safety and security at sea, which potentially affect all ongoing activities and all with consequences for the ecosystem (spills), society (human life and property), (geo)politics and existing legal agreements. Within the Dutch context, already decades ago it was agreed that the risk level at the Dutch part of the continental shelf should be maintained at the same level or preferably lowered [1].

Today, against all odds, and where land- and air-based safety targets aim at zero accidents, sea-based polices still allow the introduction of new, yet unknown risks as they are coming along with new activities developing without maintaining a clear target on the acceptable total risk level at the same time. Obviously, once such a level is set, you need to proactively check the risks of planned developments against this max level.

On security of the North Sea HCSS has recently published a report convincingly pointing towards a set of salient implications for the Coast Guard and the RNlN [2]. The next section discusses the interests at stake.

Defence, shipping, fishery and recreation

Historically, these four users have the oldest rights to using the sea. With each of them also essential for respectively our national security, our wealth and regional economies. They led to early legal documents trying to establish this right of use of the seas for trading purposes (Mare Liberum [3]), now called the “Sea Lines Of Communication”.

Defence terminology immediately connects trading with defence. This is because of how it was actually exercised in the seventeenth century, when hardly any difference existed between trading and defence. In the first half of the eighteenth century, the principle of the freedom of the seas for navigation was commonly accepted (De Dominio Maris [4]) and at that time extended with the notion of territorial waters (3 miles).

Not much has changed since then concerning the right of free navigation. Fishing rights claims were established quite soon after the first legal proposals on the free passage of shipping appeared.

Shipping

Although the right of free navigation is not challenged, the practical execution is. The intense use of the North Sea by others and given the ruling laws and policies in place, free navigation is hampered. Traffic flow is governed by the Rules of the Road at Sea (SOLAS [5]). These rules have a limited number of articles describing the ways to avoid collisions at sea and next to those they still rely on good seamanship.

Good seamanship, however, is based on a number of assumptions. Next to experienced crew, it relies on knowing your vessel’s limits and the opportunity to manoeuvre when needed, for instance to avoid unsafe wave encounters, harsh weather areas or too complex traffic situations. Spatial planning now envisages to use a larger part of the North Sea effectively limiting this exercise of good seamanship.

Along these developments, ship sizes are increasing and introduce as yet unknown safety risks. The MSC Zoe is a good example of all three issues. Would the accident have been prevented if it had timely left the TSS (traffic separation scheme) for another course? A decision based upon experience, sufficient manoeuvring space and knowing the limits of your vessel.

The introduction of a multitude of new activities at sea adds to traffic flow intensity and often to the number of people exposed at sea, for example due to the installation and maintenance of wind parks. Ship automation and decision support or in due time autonomy would ideally increase the safety of navigation, but it does require careful introduction and a different approach to Vessel Traffic Management. At the same time, these systems need to compensate decreasing experience at sea.

It is not difficult to understand that initially, all developments above increase the risks at sea. The sheer number/size of vessels, the many objects to hit following unintended drifting, the loss of manoeuvring space, the introduction of new technologies and more people present at sea require serious mitigating measures to be put in place. These growing risks form a threat to people and property, but also to the vulnerable ecosystems in the North Sea.

Legal risks could lead to claims from shipping companies if due to a lack of manoeuvring space good seamanship couldn’t save the ship and the people on it. Or in the worst case, in international law disputes the way spatial planning has affected the Mare Liberum altogether.

Fishery and recreation

On a smaller scale, but still highly important, the diminishing of fishing grounds directly hits the economic survivability of the people involved. If ecosystems are affected, this could further add to this threat. See also the other articles in this issue and upcoming ones.

Important questions are whether the space between wind turbines can possibly be used by new forms of small-scale fishing. It is less sure whether recreation has a right in its own sense – and is perhaps less important on the North Sea – to safe passages, preferably away from the main shipping routes. Potentially, recreational vessels could use the space between wind turbines, albeit less fun.

Defence

Naval vessels, although a lot less vulnerable to the diminishing manoeuvring space, will meet some of the same effects as shipping. And certainly they still need their exercise areas.

More important is the new task added to either the Coast Guard or the Navy, which concerns the protection of the new property at sea. Property that will become essential and strategically critical to our energy and perhaps food supplies. The protection of both sub-surface cables and pipes and surface critical infrastructure like transformers, floating energy islands and the renewable systems itself (tidal, fixed and floating wind) against security threats is a serious undertaking [2].

Renewables, resources and space@sea

There is no discussion that the largest North Sea spatial claims come from the need for renewables. Either fixed or floating wind, floating solar or tidal has to be installed to fulfil renewable energy requirements. Today, plans exist for about 11 GW, see added map.

What is needed to fulfil our own total energy consumption is around 150-200 GW! Roughly fifteen times the current area and an enormous spatial claim. A more than challenging task with potentially (too) much impact on safety, ecosystems, security and legal. If solar and tidal can contribute using the same area, this claim can be lowered, but not necessarily with less impact on the ecosystems.

Text continues under pictures

Renewables

The installation and maintenance of wind farms and eventually floating solar and tidal arrays introduce a serious amount of extra shipping traffic involving many people and will result in a huge permanent spatial claim. Next to the parks, transformer platforms and cables are needed and in due time perhaps energy conversion platforms.

Shipping including fishery is forbidden and thus it takes away a substantial part of their “manoeuvring” space. Estimations on how much space is needed to reach the 200 GW installed power denote a minimum of 40,000 km2 just for the wind turbines. The total Dutch part of the North Sea is 58,000 km2.

Potentially, floating solar and tidal could add to the energy production perhaps by using the areas in between the turbines. Their introduction is likely as they strongly improve the persistency of the energy supply.

Resources

Oil and gas is not gone yet and will be around for at least another twenty years. 139 platforms or subsea installations (source: OSPAR) are still around on the Dutch part of the North Sea with their accompanying local or export long distance pipelines. All in all, about 1500 constructions are still standing either above or below the surface of the North Sea. Potentially, the existing wells do not go at all and are used in the future for storage of CO2 or hydrogen.

In terms of resources, dredging aims mostly at collecting building materials, such as sand and gravel and uses and affects large bottom areas in the North Sea (see map below).

Text continues under picture

Aquafarming is already a well-known activity, for instance in Norway, and concerns both open ocean and sheltered water fish farming. Future activities could include seaweed and other sea grown resources. Apart from occupying space, aquafarming has the potential to affect the environment by either adding nutrients into the seawater or through the unwanted escape of biomaterial.

Space@sea

The above renewable activities at sea necessitate the availability of liveable space at sea. Either in the form of floating structures (islands, FPSOs or semi-subs) or fixed platforms, artificial islands or even using the larger wind turbines themselves as production facilities (for example of hydrogen).

Once the larger islands (large scale improves the viability) are in place, likely other users at sea will find advantages of sharing these facilities. Think of manufacturing e-fuels, port facilities for shipping and bunkering of these new (dangerous) fuels and installing maintenance hubs. If aquafarming comes to life, the islands could serve as hubs as well for collecting and processing these resources.

Against the background of rising sea levels, future port extensions like Maasvlakte III could be based upon floating or fixed infrastructure as well and perhaps combined with shore protection measures.

Also read: New chart shows how busy the North Sea really is

Text continues under picture

Ecosystems, shipping and safety at risk

Although ecosystems were discussed as part of the (sustainability) assessment framework, they do not form a group of clearly identified stakeholders or users. It could be said that all of us are stakeholders in conserving nature, safeguarding a sustainable future. The threat to the ecosystems can hardly be overestimated given all the mentioned activities and their potential impact.

The development of shipping related risk levels potentially suffers from the same threat. The increase in activities requires a “systematic and methodical” approach of safety modelling (text box) and significant mitigating measures to maintain the current risk level. The legal consequences of the increasing activities are to be faced and talks initiated to explore these consequences with neighbouring North Sea countries. Security awareness seems to be growing [2].

This article was part of SWZ|Maritime’s December 2021 special on spatial planning in the North Sea and written by:

References

- From “Voortgangsnota Scheepvaartverkeer Noordzee 1996” p3: ‘Wel moet worden vastgesteld dat alleen door een diepgaand onderzoek en systematische evaluatie nadere beleidsmatige aanknopingspunten kunnen worden gevonden die een bijdrage zouden kunnen leveren aan de verdere reductie van ongevalskansen en hun potentiële effecten.’

- The High Value of the North Sea, The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies, 2021.

- Hugo Grotius, Mare Liberum,1609.

- Cornelis van Bijnkershoek, De Dominio Maris, 1702.

- SOLAS, Safety of Life at Sea, 1914-1974.

Picture (top): A very complex balancing of a multitude of interests is required.