For the North Sea to continue to sustain ecosystems and the social well-being of Northern Europe, action is needed by industry and policy makers alike. This is necessary to maintain biodiversity and natural productivity in the face of growing offshore economic activity.

This week, SWZ|Maritime’s December 2021 issue comes out. With the North Sea facing ever more uses that each take up space, bringing the different interests in balance is becoming a necessity. That is why our December issue features a special on spatial planning in the North Sea. The article below was supplied to SWZ by the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (NIOZ).

The contribution of the North Sea to the economy and wellbeing of Northern Europe is quickly evolving. Well-established resource industries such as fisheries, oil and gas, and shipping are now rapidly changing in terms of their contributions to national economies. At the same time, the conservation and restoration of North Sea habitats and species is needed to help halt the unprecedented losses in biodiversity observed across our planet. Furthermore, sustainable food production is desired as well as the ability to harness renewable sources of energy to mitigate climate change.

Maintaining biodiversity and natural productivity in the face of growing offshore economic activity requires managing the North Sea as a coherent “social-ecological” system through a long-term roadmap for implementing much-needed innovations, such as renewable energy, sustainable sea food production and nature restoration. In our view, taking at least three steps will help ensure that we co-develop and successfully meet our future, shared ambition for the North Sea.

Cause-and-effect understanding of ecological impacts

Step one, ensure nature protection. The North Sea is a dynamic environment that, historically, has supported diverse food web supporting abundant populations of fish, birds and marine mammals. The region is among the fastest warming marine areas worldwide and the effects of climate change have been well documented on all levels of the food web, from floating microscopic plankton to fish to marine mammals (Quante & Colin 2016; Peck & Pinnegar 2020).

Even if nations meet international targets for reductions in atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases, warming and other climate-driven changes such as acidification will continue for decades. Inevitably, there will be ecological winners and losers in a future North Sea and information is urgently needed to design “climate ready” nature conservation actions (e.g. Natura2000 and other marine protected areas) to meet the ambitions of the EU Green Deal to halt biodiversity loss.

Step two, enable sustainable seafood harvesting. Europe is the largest single market for fish and fish products in the world (FAO, 2018) and a primary goal of the EU is to sustainably grow the European aquaculture sector and effectively manage its fish stocks to promote self-sufficiency in the domestic supply of sea food. The North Sea provides key examples of fish stocks that collapsed decades ago and that now have been rebuilt through effective management measures. The global trend in seafood supply since the 1990s is clear: harvests by fisheries have plateaued, while those from aquaculture have increased and now provide more than half of all aquatic food resources by live weight.

Aquaculture of plants and animals near the base of the food web, such as kelp and shellfish, is the most sustainable way to harvest food from the sea. The North Sea once supported large natural oyster grounds and restoration efforts are now being developed. However, an increase in “sustainable” aquaculture and restored oysters grounds will likely reduce the capacity of the North Sea to support historical fisheries for herring and ground fish such as flatfish and cod.

Also read: Thecla Bodewes Shipyards will build new research vessel for NIOZ

Van Duren and colleagues (2019) estimated that 150-200 km2 of seaweed farms could extract about five per cent of the incoming nutrients from the North Sea system with reductions in phytoplankton growth tens to hundreds of kilometres away from farms (Vilmin & Van Duren 2021). Although we can provide these estimates (within broad confidence limits), much more work is needed to make robust predictions of how aquaculture (of plants and shellfish) will impact the wider ecosystem. These limits to carrying capacity need to be understood to effectively plan sustainable aquaculture and fisheries management in a future North Sea.

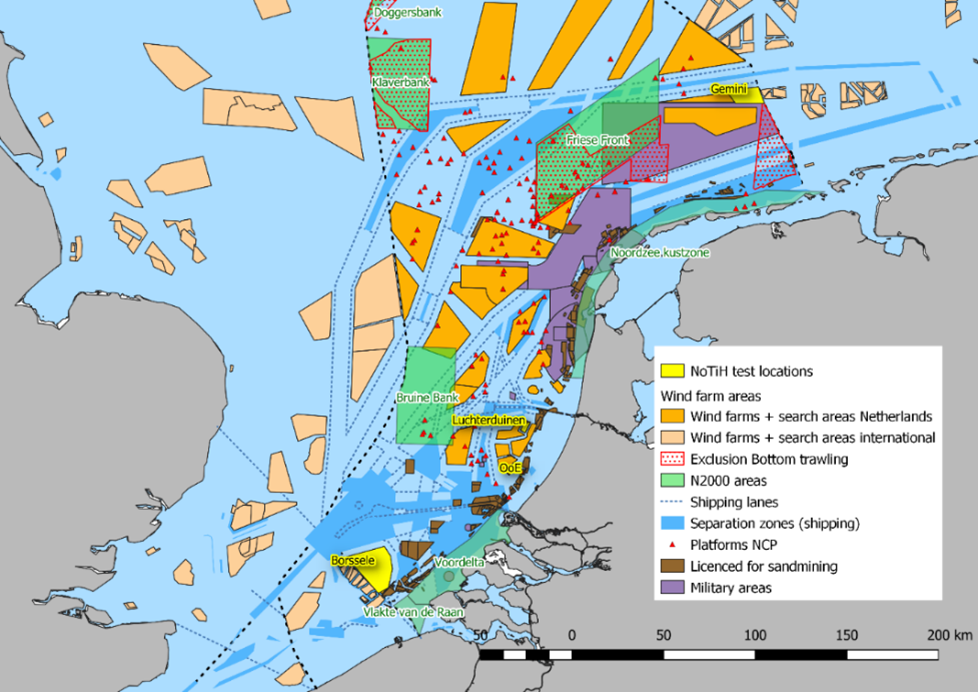

Step 3, foster nature integrated marine energy systems. Offshore wind farms will likely cover more than twenty per cent of the surface of an already spatially-squeezed Dutch North Sea in the next decades (figure 1), yet the ecological impacts of these new (and decommissioned, old) infrastructures are far from understood.

Infrastructure supporting offshore energy, such as oil and gas platforms, wind turbines, floating solar arrays, can and will have unintended side-effects. These include changes to physical processes such as wind- and tidally-driven currents and water-column mixing, that alter productivity at the base of the food web. These changes will cascade through the entire food web.

The exclusion of fisheries around infrastructures can lead to local increases in commercially important species. Some of these exclusion areas are suitable to restore reef-building populations, such as flat oysters. The infrastructures and surrounding scour protection are likely to act as artificial reefs, which increase local biodiversity, including rare species, or potentially supporting nuisance or alien invasive species.

The offshore renewable energy sector is poised to create an unprecedented human footprint in the Dutch North Sea area by 2050 and the potentially positive and negative ecological consequences need to be thoroughly understood.

Multisectoral vision and international coordination are essential

All three steps require new approaches to cross-sector marine governance that can span international borders. Most, if not all economic activities in the marine environment have transboundary impacts and, as such, should be coordinated between the North Sea’s coastal states to ensure a good environmental status. This requires international and European legal and governance frameworks to set the conditions under which the private and public sector in the Netherlands can invest in increased renewable energy, sustainable seafood and healthy ecosystems. But as the tensions and tradeoffs between energy, fisheries, aquaculture and nature conservation amply demonstrate, much still needs to be done to put such a governance system in place.

Cross-sector governance of the North Sea has to be based in a state-of-the-art understanding of the international and European environmental law and governance frameworks and the boundary conditions these set for food, energy and nature transformations in the North Sea. These frameworks are only likely to enable cross-sector regulation and innovation for multiple transitions in the North Sea if co-produced with stakeholders.

This means: co-design of legal and governance frameworks at the international, European and national levels that foster and empower new collaborations, regulation and information exchange in support of both sectoral and cross-sectoral innovation. Examples may include the (further) operationalisation of environmental principles into public and private rules, regulations and standards in support of, for instance, “regional cross-sector innovation councils”, standards and regulation in support of cross-sector information platforms and partnerships for food-energy-nature integrated “areas” and/or technologies.

Develop a shared vision through stakeholder engagement

Ongoing efforts in the Dutch North Sea Agreement have brought various stakeholders to the same table to discuss and try to develop a shared vision. Limited agreements among policymakers, NGOs, and the energy, fishing and shipping sectors have been created. Although implementing these agreements in a busy North Sea remains challenging, the cooperation and contributions made by various stakeholders were critical to the process of developing a shared vision.

This active engagement needs to be a continuous process, from the planning (co-creation, co-design) to the implementation and assessment phases. Co-creation and co-design are particularly important for programmes designed to provide science-based advice. These early engagement processes help ensure that results and breakthroughs, for instance of ecological research, are societally relevant and readily exploitable by various groups.

Also read: NIOZ and Next Generation Shipyards sign contract for research vessel Adriaen Coenen

Any form of stakeholder engagement and decision-making within marine spatial planning still needs to be science-based and solution-oriented. Science and research can offer solid, data-driven information on which to base marine spatial planning and other management and policy decisions. Such information can provide holistic insights on potential consequences of management actions such as testing scenarios to help identify desired pathways.

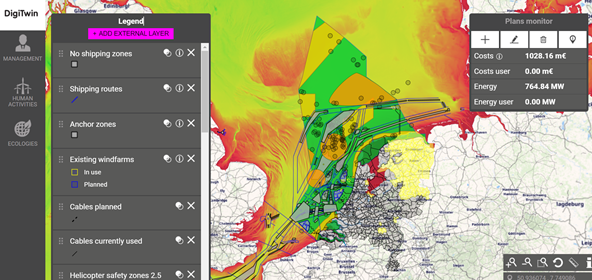

Innovative visualisation tools, such as serious gaming and digital twins are now available to support these efforts. These tools provide platforms to build on both scientific and experiential knowledge and can be useful when co-creating multisectoral socio-ecological scenarios and narratives, gathering stakeholder perspectives and experiences as well as mapping opportunities and risks, synergies and conflicts. Ultimately these tools can be used by both sectorial stakeholders and policymakers for a multitude of purposes.

Blueprint for future North Sea research

The Dutch Government, together with stakeholders and supported by a scientific committee, has mapped out a pathway to confront the three main North Sea transitions (nature, energy and food). This is supported by a significant monitoring and research programme intended to provide the basic ecosystem information required to assess the state of the North Sea and assess the consequences of changes in human use.

This monitoring and research programme (MONS) is important, but is entirely focused on the natural environment. What is required is an adjacent programme that links the North Sea ecological environment to the socio-economic environment and facilitates an appropriate, integral and workable legal framework to ensure sustainable and profitable use of the North Sea without transgressing ecological limits.

The six authors of this article are among a larger group of scientists and practitioners that have proposed such a trans-disciplinary research programme that merges knowledge and experience of academics, members of industry, NGOs, and policymakers to provide science-based advice on implementing transitions in energy, food and nature in the North Sea. The proposal (North Sea Transition in Harmony – NoTiH) received strong praise from its reviewers in early December 2021 and now enters the final decision phase in this competitive call “Research through Routes by Consortia” by NWA, the Dutch Research Agenda of the Dutch Research Council NWO.

Regardless of successful funding, North Sea in Transition Harmony serves as a blueprint for obtaining the knowledge needed to weigh the social-ecological costs and tradeoffs of these rapid North Sea transitions.

Picture (top): North Sea plankton (by Lodewijk van Walraven/NIOZ).

This article was written by Myron A. Peck of the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (NIOZ), myron.peck@nioz.nl, Simon Bush of Wageningen University, Alex Oude Elferink of Utrecht University, Serena Rivero of the North Sea Foundation, Luca van Duren of Deltares and Dick van Oevelen of NIOZ.

References

- FAO (2018). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2018 – Meeting the sustainable development goals. Rome. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Peck, M.A., & Pinnegar, J.K. (2018). The Chapter 5: Climate Change Impacts and Vulnerabilities: The North Atlantic & Atlantic Arctic, Pages 87–111, In, Barange, M., Bahri, T., Beveridge, M., Cochrane, K., Funge-Smith, S., Poulain, F. (Eds.), Impacts of Climate Change on Fisheries and Aquaculture: Synthesis of Current Knowledge, Adaptation and Mitigation Options. FAO Fisheries Technical Paper, 627.

- Quante, M. & Colin, F. (2016). North Sea Region Climate Change Assessment, Springer. 10.1007/978-3-319-39745-0

- Van Duren, L. A., Poelman, M., Jansen, H., & Timmermans, K. (2019). Een realistische kijk op zeewierproductie in de Noordzee. BO-43-023.03-005, Wageningen Marine Research, Yerseke.

- Vilmin, L.M., & van Duren, L.A. (2021). Modelling seaweed cultivation on the Dutch continental shelf. 11205769-002-ZKS-0001, Deltares, Delft.