Every time you assume an action will be taken by another party without verifying directly with them, the door to a potential accident is opened, says The Nautical Institute. A recent Mars Report illustrates the consequences of acting on assumptions. In it, two vessels collide resulting in over USD 1 million in damages.

The Nautical Institute gathers reports of maritime accidents and near-misses. It then publishes these so-called Mars Reports (anonymously) to prevent other accidents from happening. A summary of this incident:

In darkness, a coastal service container ship was leaving port under the master’s con. There was no pilot, as the master had a pilot exemption certificate. In addition to the master, there was also an officer of the watch (OOW) on the bridge and a helmsman at the wheel. The master reported the vessel’s departure to vessel traffic services (VTS). The report was received, but VTS did not give the status of traffic in the port.

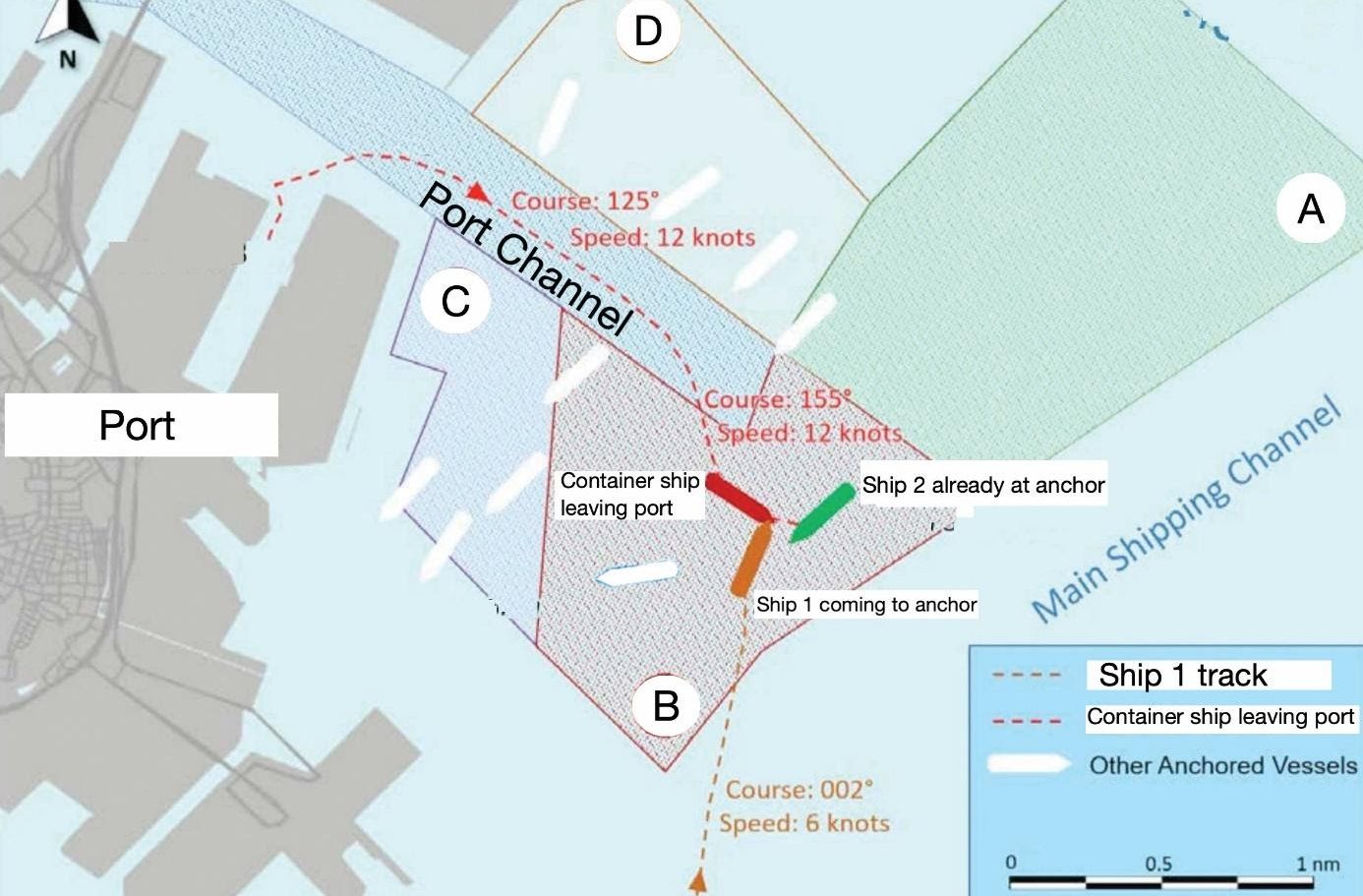

The vessel’s speed was set at near 12 knots, in accordance with port speed rules. As the vessel approached the end of the secondary port channel, the master altered course from 125° to 155° to join the main shipping channel and proceed in a southerly direction. The course would take him across the area between the secondary port channel and the main shipping channel, which was a designated anchorage area (A, B, C & D).

Not only were there several ships already at anchor in this area, but another vessel, “Ship 1”, was making way at about six knots from the south on a course of 002° and preparing to let go anchor. The master’s intention was to pass starboard to starboard with the approaching Ship 1 and between two other anchored vessels, one of which is “Ship 2” (see diagram, portrayed in full below).

The bridge team on Ship 1 assumed the outbound ship would join the main shipping channel to the north. But as they closed, they saw the outbound vessel altering to starboard. There were no radio communications between the two vessels at any time, but Ship 1 sounded the warning signal with the ship’s horn several times.

By now the outbound container vessel had come to port and it was obvious a collision would occur. Both vessels’ bridge teams took evasive actions, but to little effect. The outbound vessel hit the inbound and then careened off and collided with the anchored Ship 2 as well. No injuries were reported, but damages to all three vessels were over USD 1 million.

Advice from The Nautical Institute

- In this case, both masters assumed incorrectly what the other’s intentions were.

- Even had these vessels confirmed their actions ahead of time, the space between the two anchored ships left little room for error for the two meeting ships. Given this fact and the darkness, the decision of the outbound vessel’s master to pass between the two anchored vessels was not the best one.

- In a crowded and busy port, best practice would dictate that you should be informed ahead of time of the movements and intentions of other vessels.

- Speed was not excessive at 12 knots, but given the extreme congestion in this port and darkness, why not proceed at six knots to exit? This would give twice as much time to assess the situation and act accordingly.

Mars Reports

This accident was covered in the Mars Reports, originally published as Mars 202063, that are part of Report Number 337. A selection of this Report has also been published in SWZ|Maritime’s December 2020 issue. The Nautical Institute compiles these reports to help prevent maritime accidents. That is why they are also published on SWZ|Maritime’s website.

More reports are needed to keep the scheme interesting and informative. All reports are read only by the Mars coordinator and are treated in the strictest confidence. To submit a report, please use the Mars report form.