The Maritime Master Plan presented by the Dutch maritime sector is desperately needed, argues SWZ|Maritime’s Editor-in-Chief Antoon Oosting. Both sectors are currently under great pressure due to the corona crisis, competition from China in particular and the fight against global warming. The plan, however, does need political support.

In every issue of SWZ|Maritime, Oosting writes an opinion piece about the maritime industry or a particular sector within it. In the November 2020 issue, he discusses how the Dutch government will have to take a leading role to protect its shipbuilding and shipping industry.

The Maritime Master Plan was presented on Tuesday 3 November. The shipbuilding industry in the Netherlands is facing the drying up of orders, and shipping is at risk of disappearing from the Netherlands if it cannot meet the increasingly stringent requirements for reducing CO2 emissions in particular.

Now, only a “Big Leap Forward” is appropriate to show that the sector can indeed meet the challenges of the future. At the end of April, the sector already launched a Maritime Recovery Plan, which has now been developed into a Master Plan. This should result in thirty emission-free ships and five retrofits by 2030. The development and construction of these ships should enable the Dutch shipbuilding industry to take a considerable lead over international competition. At the same time, it should convince Dutch shipowners and other ship owners, such as governments and institutions, to have their ships developed and built in the Netherlands for the necessary greening of their fleet.

The Dutch government will be the first to sail emission-free ships

‘The Netherlands must become a world leader in sustainable shipbuilding and shipping,’ says Rob Verkerk, who was Commander of the Royal Netherlands Navy from September 2014 to September 2017 and currently is Chairman of Nederland Maritiem Land, the lobbying organisation of the broad Dutch maritime sector. ‘With this initiative, the Dutch government will be the first to sail emission-free ships and we will strengthen our international competitive position.’

Government as launch customer

The implementation of the Maritime Master Plan cannot be done without the support of the (national) government, which will have to contribute to the financing of the almost 100 per cent emission-free ships. The aim of the plan is to set up some thirty pilot projects for both sea and inland shipping. Because they regularly have to renew ships in their fleets, the Royal Netherlands Navy and Rijkswaterstaat (the executive agency of the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management) have expressed their willingness to participate in these pilot projects.

The problem is that the current financing instruments are not sufficient. The development and application of emission-free propulsion systems, such as those using methanol, ammonia and hydrogen in combination with, or completely electric, is, of course, often about technology that has yet to prove itself in practice. For example, the first battery fires and explosions (in Norway) on partly electric ships have already been reported. The search for the right, workable and safe solutions requires time and money, money that shipyards in particular do not currently have due to their emptying order books.

Sector requires co-financing

The sector expects to be able to finance up to 75 per cent of the development and construction costs of emission-free ships itself. The remaining 25 per cent will require cofinancing. It is expected that emission-free ships will be built in the longer term, but without cofinancing, the whole plan is guaranteed to be considerably delayed and the 2030 target will become unattainable. The maritime sector is therefore asking for EUR 250 million from the National Growth Fund or the European Recovery & Resilience Fund (RRF).

Without cofinancing, the 2030 target will be unattainable

During the online innovation event of the maritime Topconsortium Kennis & Innovatie (Knowledge & Innovation), the sector explained how it sees the further development of the required sustainable technologies. Based on the joint development of the required knowledge and technology, the maritime sector wants to ensure that the government, as a launch customer, can sail emission-free vessels by 2030.

The shipyards want to start retrofitting five existing ships and using alternative fuels in order to be able to sail cleaner straight away. Parallel to this, the sector is working on digitalisation aimed at smart shipping and smart maintenance.

From seagoing vessels to inland navigation

The cooperation between knowledge institutes, the manufacturing industry and the government as launch customer should lead to vessels of various sizes and for various applications, varying from the Rijksrederij (Rijkswaterstaat and Coastguard) and Defence (Royal Netherlands Navy) to commercial vessels, for both inland and ocean shipping. Examples include electric sailing, using hydrogen or methanol, the use of lighter materials such as aluminium or innovative ship designs.

For the navy, this mainly concerns its seagoing support vessels. From 2024 to 2034, the naval training vessel, the submarine support vessel, the inland diving vessels, hydrographic survey vessels and the Caribbean support vessel are scheduled to be replaced. By making these vessels suitable for sailing on methanol or other biological or synthetic fuels, a considerable (ten to fifteen percent) reduction in CO2 emissions could already be achieved.

Fuel available worldwide

In the long term, up to 2050, the navy expects to emit around thirty per cent less CO2. The big question is what to do with the capital ships such as the frigates, submarines and logistic support vessels such as the Karel Doorman, Rotterdam and Johan de Witt. They must be able to operate worldwide, which means that the necessary fuel must also be available worldwide.

This is a long way from being the case for alternative fuels in particular. There is also an important technological problem, because not all alternative fuels provide enough energy to guarantee larger ships the required speed.

As far as logistics are concerned, the Rijksrederij has a somewhat easier time of it. It manages, mans and maintains a hundred or so specialist and very diverse ships for Customs, the Coastguard, the Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality and Rijkswaterstaat. They have an average age of 23 years, which means that a number of ships have to be built every year.

As sustainable as possible

The starting point for newbuilds is that every ship should be able to sail as sustainably as possible and, where possible, emission-free. The Rijksrederij expects that the smaller ships for inland waterways can often be fitted with batteries, while the larger ships for both inland and coastal waters could be fitted with hydrogen fuel cells. For the larger seagoing vessels, the Rijksrederij believes that methanol will prove to be the most suitable alternative fuel.

In addition to newbuilds, the Rijksrederij also wants to start experimenting with pilot projects in the form of retrofitting as soon as possible.

For the larger seagoing vessels, the Rijksrederij believes that methanol will prove to be the most suitable alternative fuel

In addition to the government, Dutch shipowners are also closely involved in making their fleets more sustainable. The Master Plan mentions passenger (ferries), short-sea, offshore, inland waterway and fishing vessels and workboats. The shipowners united in the Dutch shipowners’ association KVNR are thinking in particular of the use of alternative fuels such as hydrogen, green methanol, synthetic LNG and the application of promising energy-saving technologies such as nozzles (around the ship’s propellers).

Of the 250 million euros requested by the compilers of the Master Plan, 70 million is earmarked for the development and strengthening of the maritime ecosystem; the development of knowledge about the application of alternative, CO2 -free fuels such as methanol, hydrogen and fuel cells. The rest is mainly for the launch customer projects to build cleaner ships for the navy, the Rijksrederij and commercial shipowners in sea and inland shipping and the five retrofits of commercial ships of Dutch shipowners.

Growth manufacturing industry

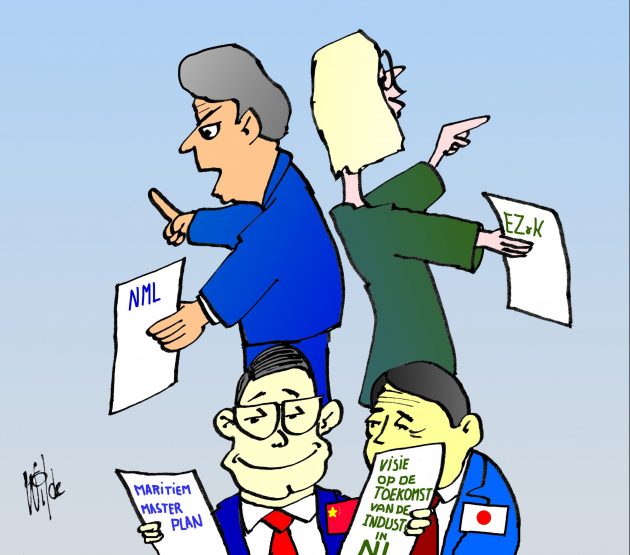

With this, the plan deserves the predicate of ambitious. It comes as quite a surprise then that on the day of the presentation of the Master Plan, State Secretary Mona Keijzer of the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate issued a press release under the heading “Cabinet is committed to structural growth of the Dutch (manufacturing) industry” in which not a single word is said about the maritime manufacturing industry.

Dutch industry now accounts for almost ten per cent of employment and around twelve per cent of the GDP. According to State Secretary Keijzer, the Netherlands has a strong presence in various international markets. These are industrial companies in sectors such as food, chemicals, mechanical engineering and semiconductors. But this also applies to the intersection of industry and the agricultural sector, with the maritime sector also being mentioned in passing.

The fact that the Dutch maritime sector, with 21,265 companies, 263,000 people and an added value of EUR 23.2 billion (NMT 2019 figures), makes a significant contribution to our GDP, is overlooked in this press release from the Ministry, for the sake of convenience.