Blind pilotage cannot be improvised and best results come only if these skills are constantly practised before they are needed. This is the advice given by The Nautical Institute after a ferry in fog collided with a sailing yacht, resulting in the latter’s sinking.

The Nautical Institute gathers reports of maritime accidents and near-misses. It then publishes these so-called Mars Reports (anonymously) to prevent other accidents from happening. A summary of this incident:

A double-ended ferry that ran between two ports, Red and Blue, was underway towards Blue port in fog. The ferry had a central bridge and control consoles at either end which allowed it to run between the two ports without having to turn 180°. For navigation purposes, the designated bow of the vessel changed with the direction of travel; the “Blue end” being the bow on passage to Blue port and the “Red end” being the bow on passage to Red port. A manual switch on the consoles allowed the electronic chart system (ECS) to display the correct heading.

The master had the con during the passage and stood next to the helmsman in front of the radar and the ECS at the Blue console. Another officer and a dedicated lookout were also on the bridge. The officer was standing at the Red control console at the other end of the bridge and used the radar and ECS to provide the master with navigation and collision avoidance information. The lookout was stationed on the port bridge wing.

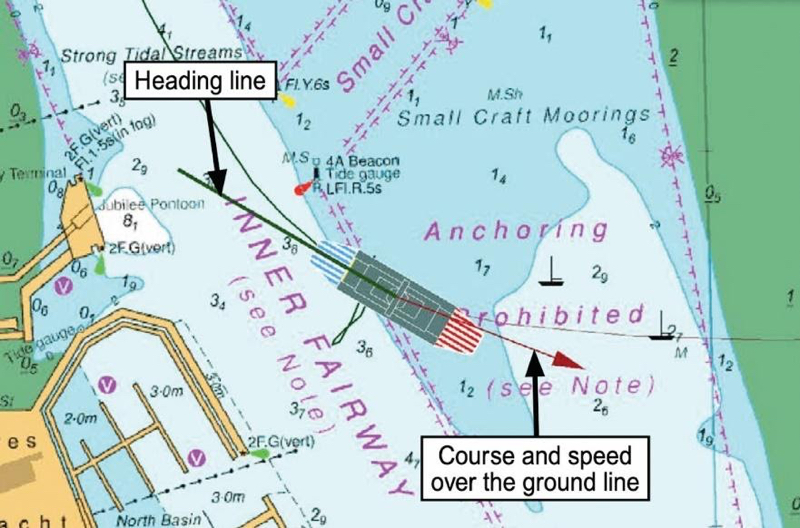

As the ferry approached Blue port, the helmsman was having difficulty maintaining the required course, and the ferry started to swing to port in the channel. He immediately raised his concerns and the master decided to take control of the vessel’s steering and propulsion (diagram 1). As he did this, visibility reduced to less than 200 metres.

Diagram 1. The master takes control of the vessel’s steering and propulsion.

The assisting officer remained at the other end of the bridge and continued to relay positional information and messages from the deck lookout, whose radio calls were becoming more frequent and urgent.

The master managed to arrest the vessel’s swing briefly, but the ferry started to swing to port once again and the ferry left the inner fairway to the east. At this point, visibility reduced still further and the bridge team were no longer able to visually identify the shoreline or navigation marks.

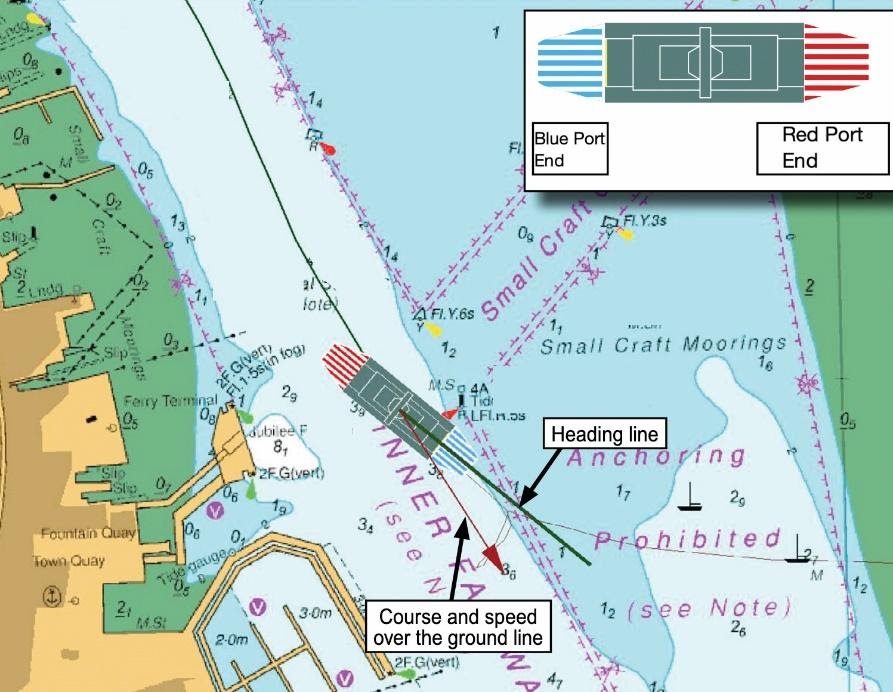

By now the vessel had turned through about 220° from its original heading and was stopped very briefly in the water, as in the diagram portrayed at the top.

The master decided to abort the berthing and manoeuvre the ferry back into the channel and out of Blue port. Believing he was still in the same orientation as before, he put the propulsion system astern and ran to the Red end of the bridge and immediately increased the propulsion power.

He asked the officer to give him a course to steer into the inner fairway, but this added to the confusion because now the vessel was increasing speed toward the yacht moorings on the east side of the harbour.

Shortly thereafter, the ferry collided with a moored sailing yacht at about 6 knots, sinking it. The master stopped the engine thrust, but the ferry continued toward the shoreline and grounded on soft mud about 130 metres from shore.

Investigation findings

Some of the report’s findings include:

- The collision and grounding occurred because the master became disorientated in the fog and inadvertently drove the ferry in the wrong direction.

- When the master took over operating the controls, the oversight of operations was lost. The members of the bridge team started to act in isolation and did not adequately support the master.

- The ergonomic layout of the navigation equipment did not support single-person operation of the ship’s controls from the side of the console.

- Another crucial element of bridge resource management (BRM) is to challenge, if need be, a decision taken by another member of the team, even the master.

- The electronic chart system relied on a manual switch to provide correct heading information (to properly show which end is the bow). This switch was not operated by the master as he rushed from the Blue end console to the Red end console.

- Overcome by tasks and disorientated, the master focused on the ECS and used the information displayed as a basis for his decision-making. The erroneous heading information being displayed supported the master’s belief that the ferry was headed back into the channel.

The Nautical Institute concludes by saying that ‘the essence of BRM is task delegation and teamwork. These were critically lacking in this instance.’

Mars Reports

This accident was covered in the Mars Reports, originally published as Mars 202053, that are part of Report Number 336. A selection of this Report has also been published in SWZ|Maritime’s November 2020 issue. The Nautical Institute compiles these reports to help prevent maritime accidents. That is why they are also published on SWZ|Maritime’s website.

More reports are needed to keep the scheme interesting and informative. All reports are read only by the Mars coordinator and are treated in the strictest confidence. To submit a report, please use the Mars report form.