Passage plans need to be revised according to weather according to The Nautical Institute. The organisation gives this warning after a RoRo had its cargo topple over in heavy weather.

The incident was discussed in a recent Mars Report. The Nautical Institute gathers reports of maritime accidents and near-misses. It then publishes these so-called Mars Reports (anonymously) to prevent other accidents from happening. A summary of the incident with the RoRo vessel:

A shortsea ro-ro passenger and freight service operated up to seven sailings per day with a crossing time of about two hours. The ship’s deck crew were split into a day shift, which was led by the day master, and a night shift led by the night master.

In the evening, the day master sent an e-mail to all ship departments warning of a forecast of heavy weather that night and the following morning. All loose gear was to be secured prior to the ship’s scheduled departure at 20.20.

The deteriorating weather conditions meant the vessel arrived at its destination 55 minutes behind schedule. The next departure was postponed due to the prevailing weather conditions, which were close to the company’s limits for entering and leaving the ports.

During the cargo loading operations, the master discussed the lashing requirements with his loading officer. It was decided to lash the freight vehicles parked at the fore and aft ends of each vehicle lane and all unaccompanied semi-trailers with two lashings (one either side).

At 05.15, loading was completed with forty accompanied freight vehicles (mainly articulated vehicles) and 46 other vehicles. When the vessel sailed, the wind was close to the company’s limits for departing port and the master experienced some difficulty manoeuvring the ship’s bow through the wind. Once in open water, the ship’s stabilisers were deployed, the autopilot set to the ship’s standard planned course of 073° and the ship was brought up to its full sea speed of 21 knots.

Soon after leaving port, the vessel experienced several large rolls. The wind was blowing between 40 and 50 knots gusting to 60 knots; the waves were very large from the same direction, causing the ship to roll and yaw. Following a discussion with the master, the officer of the watch (OOW) altered course to port and brought the ship on to a course of 055° with the aim of easing the motion.

A few minutes later, the OOW altered course to starboard and brought the ship on to a course of 060°. A little later, the vessel rolled 20° to starboard, then yawed violently to starboard, achieving a rate of turn in excess of 100° per minute. The ship then took a larger roll to port of just over 30°. During the 30° roll, several of the freight vehicles and unaccompanied semi-trailers on the vehicle decks moved and some toppled over. In the engine room, a lubricating oil low-level trip activated on one of the ship’s four main engines, causing it to shut down.

The OOW altered the ship’s heading to 057° and very quickly the master arrived on the bridge, followed shortly afterwards by the chief officer and the day master. The OOW briefed the master while the chief officer used the ship’s CCTV system to assess the condition of the cargo on the vehicle decks. The chief officer saw that several vehicles had toppled over and informed the master. The ship was placed into hand steering and brought round to starboard to a course of 085°. The OOW handed the con to the master and went to assist on the vehicle deck.

Within 90 minutes, the vessel had been brought to shelter and docked.

Investigation findings

The official report found that, among other things:

- The passage plan was not altered to minimise the potential effects of the prevailing and forecast weather conditions and the night master’s intent to continue on the altered course was not clearly communicated to the OOW. Either action could have avoided heavy rolling.

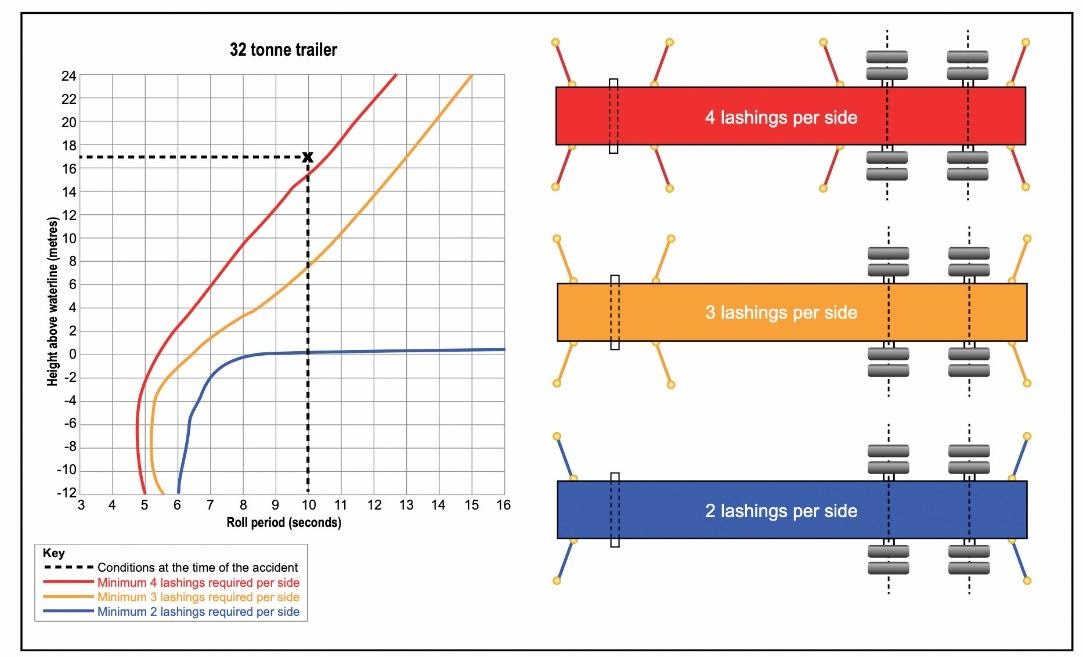

- The freight vehicles, secured with one lashing on either side, were not lashed in accordance with the guidance provided in the MCA’s guidance, “Ro-Ro ships: stowage and securing of vehicles code of practice”. For the conditions experienced, four lashings on either side would have been required.

- Passengers remained in their vehicles during the passage, endangering themselves and compromising the safety of other passengers and crew. This practice is not unique to this company and requires industry-wide collaboration to eliminate it.

Advice from The Nautical Institute

- Passage plans need to be revised according to weather; Mother Nature is the boss.

- Best practice dictates that passengers and truck drivers exit their vehicles before transit.

- MCA guidance for lashing freight vehicles can be seen in the figure below.

MCA guidance for lashing freight vehicles.

Mars Reports

This accident was covered in the Mars Reports, originally published as Mars 202048, that are part of Report Number 335. A selection of this Report has also been published in SWZ|Maritime’s October 2020 issue. The Nautical Institute compiles these reports to help prevent maritime accidents. That is why they are also published on SWZ|Maritime’s website.

More reports are needed to keep the scheme interesting and informative. All reports are read only by the Mars coordinator and are treated in the strictest confidence. To submit a report, please use the Mars report form.