The energy transition requires a lot of resources and materials. ‘Eventually there will be a shift from oil and gas to mining the metals you need,’ says Wiebe Boomsma, Manager R&D at Royal IHC. ‘After all, wind turbines, solar panels and batteries really don’t grow on trees.’

Deepsea mining requires a full mining value chain to take off: the right licences and permits, deposits, the harvesting technology (vehicle, transport system, mining vessel), processing and refining of the materials and the right logistics. Over the past twelve years, Royal IHC has been developing an integrated deepsea mining solution, comprising a crawler and riser system as well as mining vessel designs to harvest polymetallic nodules from water depths of up to six kilometres.

SWZ|Maritime spoke to Boomsma and his colleague Laurens de Jonge, Manager Marine Mining at Royal IHC, to discuss the deepsea mining landscape as well as the mining solution developed by the company. In this first in a series of articles, we look at the different deposits, the development of offshore mining regulations as well as the relation between deepsea mining and the energy transition.

Deepsea Deposits

Royal IHC started investigating deepsea mining as early as 2008. ‘A return to its roots,’ jokes Boomsma, because the company IHC was formed in 1943 to supply a fleet of large bucket dredgers for offshore tin mining in Indonesia after the war. Today, it is the company’s smallest business unit after its bigger brothers dredging and offshore.

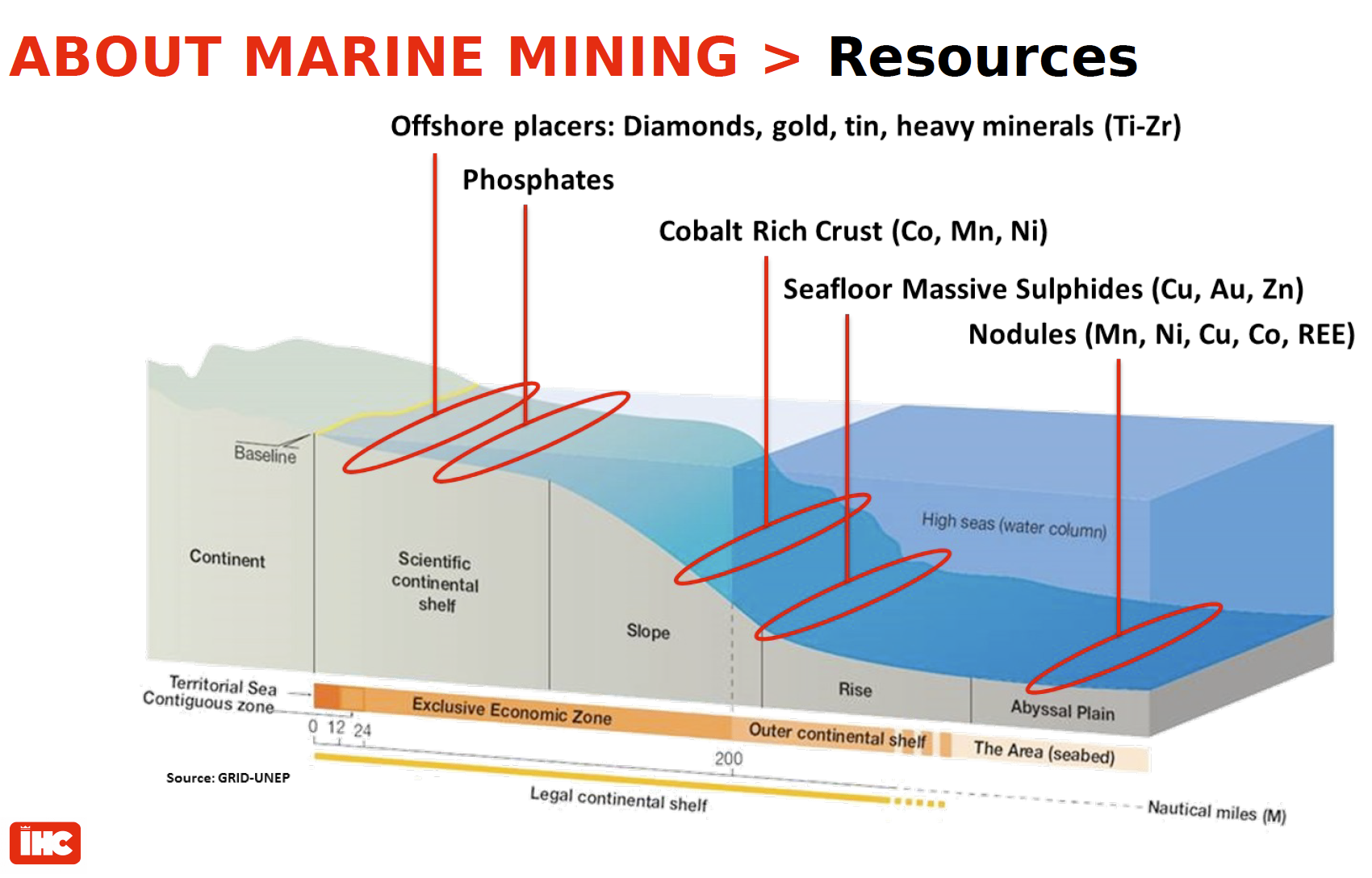

‘There are three main deepsea deposits of which the first are the cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts,’ says Boomsma. ‘They can be found on the slopes of sea mounts and they contain high quantities of cobalt as their name suggests as well as manganese and nickel. They are in this respect similar to polymetallic nodules found deeper, but the nodules are a kind of potato-shaped rocky boulders, while the cobalt-rich crust is a hard layer that really needs to be excavated.’

Underwater deposits and where to find them (by Royal IHC).

The Seafloor Massive Sulphides (SMS) follow the cobalt rich crust when looking further into the ocean. When it comes to deepsea mining, the early focus was on these SMS, which are volcanic areas with hard soils and often inhomogeneous and relatively small deposits. ‘This was mainly because of what’s inside: mostly copper and precious metals such as gold and silver,’ explains De Jonge.

‘Copper was a hot item at that time with volatile prices and China emerging and boosting demand. So the focus on SMS was a bit hyped to my opinion, comparable to the gold rush, fuelled by opportunism. It has been difficult to find larger deposits in non-active areas, which would be feasible for exploitation. In the meantime, land based copper mines have stabilised the supply, after which the focus shifted to polymetallic nodules.’

The focus on SMS was a bit hyped to my opinion, comparable to the gold rush

Polymetallic Nodules Are a Strategic Choice

‘Polymetallic nodules are much more a strategic choice as they contain metals, nickel and cobalt in particular, that are crucial for the energy transition, specifically for EV batteries. These will prove valuable on the longer term,’ says De Jonge.

Cobalt is on the European Union’s Critical Raw Materials (CRM) List, which contains raw materials that are considered of high importance to the EU economy and of high risk associated with their supply. Nickel is already a candidate for this list ‘and it is expected it will find its way onto the list within the next couple of years as it becomes harder and harder to obtain high grade nickel from land resources,’ adds Boomsma.

He continues: ‘Polymetallic nodules on the ocean floor can be considered a full-fledged copper and nickel mine. In addition, because the nodules can supply different metals and markets, they are more resilient to market fluctuations, allowing for a more robust business case.’

Polymetallic nodules on the ocean floor can be considered a full-fledged copper and nickel mine

Boomsma: ‘We feel the metals in polymetallic nodules will be valuable in the future, cobalt and nickel for example, because they are needed for the batteries in electric cars. Copper on the other hand for wind turbines and upgrades of the electrical grid for instance. A wind turbine contains some three tonnes of copper per megawatt. Nickel, cobalt and manganese are also used to create new high-tensile and stainless steel alloys. This means less steel is needed to reach a higher strength, which also helps reduce the weight of constructions. This makes it a formidable competitor for aluminium, depending on the use of course.’

Opportunity to Do It Properly

Acquiring the right to mine in the deepsea, is linked to sustainability. Boomsma: ‘We are in a unique position. Deepsea mining is not being done yet, we now have the unique opportunity to set it up and execute it properly. While ordinary mining is an evolution of many years, regulations are always lagging behind developments.’

‘Moreover, when mining takes place on land, it is subject to national rules and regulations. Deepsea mining would take place in international waters, outside the jurisdiction of any nation state. Therefore, the rules must be determined and coordinated at an international level. In any case, the opportunity is there, whether it is carried out properly remains to be seen.’

ISA

The International Seabed Authority (ISA), based in Kingston Jamaica is developing exploitation rules and regulations, but this is ‘a lengthy and political process,’ says De Jonge, who has joined the Dutch delegation to the ISA for the last few years. ‘Sometimes I think, can’t someone decide already? But the ISA is a real organisation of nation states, who have to decide on consensus, comparable to the UN in New York. It just takes time to come to a treaty all 167 states can agree on and can also count on approval by all the other stakeholders and the public, mostly represented by observer non-governmental organisations (NGOs).’

Can’t someone decide already?

‘It was envisaged to come to a result in 2020, but it has become clear this will probably take longer. Quality, especially in the field of limiting the environmental impact has priority for the time being, not speed. We want to do it right.’

Exploration Licences

Offshore mining now mostly takes place in countries’ Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) under national regulations. De Jonge: ‘If you want to work in international waters, you have to apply for an exploration licence at ISA.’ China currently holds the most licenses for international waters (three out of the eighteen granted for polymetallic nodule exploration).

A contractor willing to acquire a licence must do so under a sponsoring state. The Netherlands is not yet a sponsoring state for the licences now awarded. This does not mean Dutch companies are not involved. In June 2019, the Canadian company DeepGreen announced it had entered into a partnership with Allseas, for example, to research harvesting of deepsea metals under the sponsorship of Nauru.

Green Dilemma

‘There is now a lot of resistance from environmental groups saying that it should only be done if the consequences are one hundred per cent known,’ says Boomsma. ‘But of course in reality, no-one can ever be one hundred per cent sure. This also drives delays. On the one hand, environmental groups are in favour of renewable energy, but on the other they have difficulty mining the materials for it. This is what you can call the Green Dilemma: the energy transition requires a lot of resources and materials, eventually there will be a shift from oil and gas to mining the metals you need. After all, wind turbines, solar panels and batteries really don’t grow on trees.’

Picture (top): Laurens de Jonge (left) and Wiebe Boomsma (by Royal IHC).

This is the first in a series of articles about deepsea mining. The next article will be published next week and will describe the riser system Royal IHC has developed as part of its deepsea mining solution. The full article will also be published in SWZ|Maritime’s January issue.