Very slowly, since 24 February 2022, The Hague found out that Putin had started a war against the Free West and the Netherlands might also have to start worrying about its freedom and prosperity. So an “envoy” for the maritime manufacturing industry has now been appointed to map out what it will take to keep our shipbuilding industry alive for the future.

In every issue of SWZ|Maritime, SWZ|Maritime’s editor-in-chief Antoon Oosting writes an opinion piece under the heading “Markets” about the maritime industry or a particular sector within it. In the June 2023 issue, he discusses how the war in Ukraine has put the Dutch shipbuilding industry back on the political agenda. Please note, this was written before the revised Maritime Master Plan was awarded funding.

It is astonishing, to say the least. Despite the nationally funded annual Maritime Monitors, with a wealth of data on the sector, and the Maritime Master Plan prepared in recent years (2020-’22) by the sector itself, with financial support from the same Dutch government, this was not enough for a contribution from the National Growth Fund in April last year.

Everything stored in such reports appears to disappear into the proverbial desk drawers without being read by officials and especially not by politicians. Shipbuilding and shipping, like so many manufacturing, trade and transport industries, simply do not have the interest of politicians. Unless there is tax money to be earned from it with increasingly stringent environmental measures. But then again, as Parliament and Government, you cannot just give in to arguments from an industrial sector. If you want to start doing that at all, a politician needs fig leaf to show that Parliament and government are “deliberately” arriving at “new policy” through “progressive insight”.

Also read: Shipping decarbonises, but will Rotterdam industry survive?

Wonderful Maritime Master Plan

Responding to the obviously widespread desire that shipbuilding and shipping also contribute to the fight against global warming, the maritime sector had submitted a magnificent Maritime Master Plan early last year, hoping for a contribution of 366 million euros from the National Growth Fund. But that did not materialise at that time.

The decision to reject the grant application was made in mid-April last year. ‘We really did not see this coming and I am also very disappointed about it,’ said chairman of lobby organisation Nederland Maritiem Land (NML), former naval force commander Rob Verkerk, in a post on NML’s website. In an article by Schuttevaer in early May last year, the NML chairman noted that the implementation of the Maritime Master Plan has been severely delayed as a result, but as befits a good military man: ‘The ambition remains’.

This hefty delay comes on top of the economic woes caused by the Covid crisis in shipbuilding. As a result, many potential clients postponed their newbuilding orders in anticipation of seeing how the world would develop after corona. The original Master Plan, which had thus been worked on for almost two years, first in the form of a Maritime Recovery Plan to shake off the damage done by the Covid crisis and then as a Master Plan to respond to the desired greening, was supposed to deliver a total of fifty zero-emission ships by 2030.

‘Shipping is responsible for three per cent of CO2 emissions globally and so we need to become more sustainable,’ the NML chairman said in May last year. The industry – shipbuilders, suppliers, shipowners and research institutes – declared their willingness to invest more than a billion to build those zero-emission ships. But to actually make it happen, 366 million government subsidy from the National Growth Fund was also needed.

Also read: Dutch Maritime Master Plan wins EUR 210 million in funding

Subsidy for unprofitable top of the investment

Everyone, at least in the business world, understands that new, emission-free technologies cost a lot more money than the existing internal combustion engine, in shipping still almost always powered by fuel oil or diesel. A merchant ship simply cannot cost too much in new construction or purchase otherwise there is simply no money to be made.

So the government’s helping hand is needed to finance the uneconomic top of the investment in an emission-free ship. Low-emission ships are now also being built elsewhere in Europe, especially in the Nordic countries and Germany, but only with special subsidies.

The first Maritime Master Plan envisaged building twenty sample ships for the Royal Navy and the Department of Public Works (Rijksrederij) and thirty for civilian shipowners.

Verkerk and the other drafters of the Master Plan were planning to sit down with the committee, which gave the application a negative assessment, to find out what was lacking in the proposal. In part, it had already let the planners know. The plan was not considered concrete enough and the assessors did not always go along with the submitters’ assumptions.

Early this year, the sector submitted a new Maritime Master Plan for an application from the National Growth Fund. In it, the targets were adjusted slightly. Where previously there was talk of fifty emission-free ships, the goal is now ‘to develop, build and operate forty reliable and competitive climate-neutral demonstration ships’. These ships should run on alternative fuels such as hydrogen, methanol and LNG with CO2 capture. These vessels should be for coastal and inland navigation, wetland construction, offshore wind and maritime safety.

Also read: In SWZ|Maritime in June 2023: Dutch shipbuilding and the last Maritime Monthly

Shipbuilding sector agenda

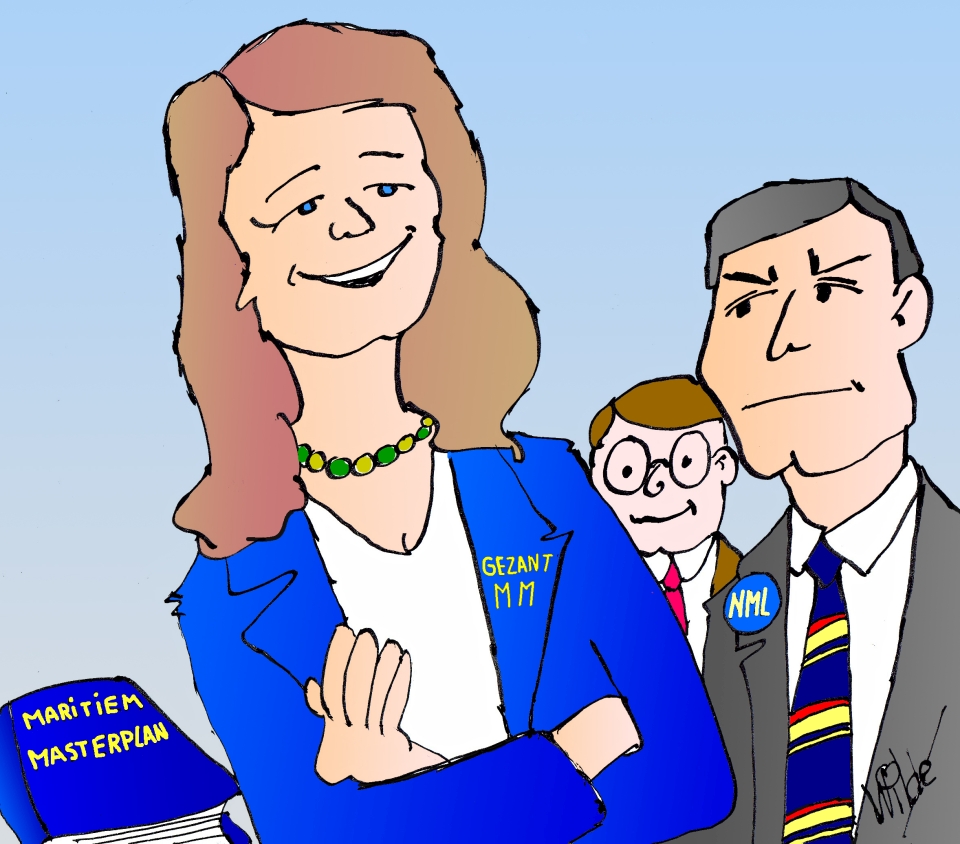

On 13 March, Minister of Economic Affairs and Climate, Micky Adriaansens, co-minister of Rob Jetten, announced that she wants to draw up a sector agenda for the maritime manufacturing industry including naval construction. She simultaneously announced that she had enlisted Delft mayor and former Minister of Education, Culture and Science Marja van Bijsterveldt to take the lead in this process.

Meanwhile, a Round Table meeting was held on 14 March, chaired by Minister of Infrastructure and Water Management Mark Harbers and attended by State Secretary of Defence Christophe van der Maat and Adriaansens herself. On 11 May at the annual meeting of Netherlands Maritime Technology (NMT) at Damen Shiprepair in Amsterdam-North, Van Bijsterveldt made her first public appearance.

A native of Rotterdam, Van Bijsterveldt is fortunately not unfamiliar with the sector, as she has family members who are active in maritime supply. According to her, the government has now also realised that preserving and strengthening the maritime manufacturing industry is essential for the successful implementation of the energy transition and climate adaptation in the Netherlands with the construction of many more offshore wind turbines.

In addition, there is growing awareness in Parliament and the government that national security also depends on whether Dutch shipbuilding can provide the ships that can parry Russian attacks on the underwater infrastructure of cables and pipelines on the North Sea floor.

Having previously cut a crucial cable between Norway and Svalbard, the Russian navy has now been mapping cable networks off the coasts of Western Europe for months. And the Royal Netherlands Navy just stood by and watched it happen, as it does not have the ships to take effective action against it.

What it takes

The sector agenda should be ready by September. In the meantime, Van Bijsterveldt is constantly travelling around the country to consult with entrepreneurs and other industry parties. This should provide further analysis of the sector and answers to the question of what is needed to meet those future demands from government and society. And what the threats in the form of unfair competition are.

In doing so, Van Bijsterveldt also emphatically wants to look at other countries and what they are doing to support their maritime industry. ‘There is a lot of knowledge in the sector that we would like to exploit,’ Van Bijsterveldt said on behalf of the government.

The maritime manufacturing envoy’s first impression on 11 May was that the Dutch shipbuilding sector still constitutes ‘real Dutch Glory’. ‘The sector has a lot of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and family businesses with an often very long tradition. The passion and love for the profession is something we can all be proud of, as well as that we still have this industry,’ Van Bijsterveldt said.

In the talks up to that point, she said a number of points kept recurring. The call for a level playing field, global fair competition, the government’s procurement policy that does not always look first at what Dutch shipbuilders have to offer, concern about sufficient supply of personnel and spatial planning. ‘Make sure there remains room for shipbuilding and the maritime manufacturing industry in the licensing policy,’ Van Bijsterveldt said.

Also read: Plenty on the table, but inland navigation is in motion

Better cooperation needed

She also had the necessary criticism of the maritime sector. For instance, there are a lot of organisations that make the sector too fragmented. ‘It is a stubborn sector in which seeking cooperation is sometimes difficult. The sector could operate more successfully with better cooperation,’ is her impression.

The fragmentation also makes the sector weak towards the government. As far as she is concerned, improvements in this are necessary to make the sector future-proof, so that in the future there will still be something to be gained from building ships in the Netherlands.

Also read: Northern Dutch shipyards compete for major fleet replacement