It is clear that the European large shipbuilding industry is struggling. What can we say about where we are now when we look at what was being built by European yards around the end of last century and what we are doing today? Do we still have a position in the world of merchant marine, the business of building cargo ships of various types?

This article appeared in SWZ|Maritime’s June 2023 shipbuilding special and was written by long-time SWZ editor and former Managing Director of Lloyd’s Register London Willem de Jong, willem.dejong3@gmail.com. He asks himself whether Europe’s large shipbuilding is at a crossroads or approaching the end of the road.

The Secretary General of the European Shipbuilders’ Association (SEA Europe), spoke about the competitiveness and resilience of the European maritime technology industry at a recent conference as follows: ‘The European maritime industry is facing both a competitive (price differences with global competitors on average between thirty to forty per cent) and resilience challenge (dependence on a few niche markets makes the sector vulnerable and less resilient). What we really need, on top of R&D support, is to create a true global level playing field, reinforce Europe’s maritime industrial capacity and supply chain and promote Europe’s technological sovereignty.’

In view of this important subject, it seems useful to present some statistical information on the development of the European shipbuilding industry since the end of last century.

Also read: In SWZ|Maritime in June 2023: Dutch shipbuilding and the last Maritime Monthly

The 2000 outlook and figures

The Shipbuilding Annual Review issued by Drewry Shipping Consultants in November 2000 contains interesting statistics regarding the European shipbuilding situation and its position in the world. As so often in the past, at that moment in time, the world’s shipbuilding industry faced a period of overcapacity.

According to Drewry, the crude question was: Which shipbuilders will survive and who will not? At that time, Japan and Korea were still the dominant players, with China and Europe having about a comparable market share in gross tonnage figures.

Drewry’s prognosis for the years up to 2010 for the main shipbuilding areas was about as follows: Japan building added value ships for the world market and so called market ships (tankers and bulkers) for the domestic market; Korea obtaining a dominant position in market ships whilst gradually entering the added value ship market; China being the fast rising competitor in the market ship sector en-route to an ultimate number 1 ranking.

For Europe, the prognosis was a gradually lower market share, with some yards having to close whilst others hanging on to prestige business such as cruise, other passenger and sophisticated ships. European yards would further have the advantage of their ties with local and near sea business providing opportunities for various types of small and specialised ships.

The Drewry report also included an overview of the EU shipbuilding policy in 2000, summarised as follows:

- Keep to OECD Agreements and fight for a level playing field with the Asian competitors.

- Phasing out operating aid and bringing shipbuilding in line with other industries.

- Improve the industry’s competitiveness and productivity.

- Under strict rules, the EU would continue to allow forms of restructuring, investment and R&D aid.

In DWT terms, the report provided the following statistics regarding the European share of the worldwide deliveries of the various ship types between end 1998 and mid 2000:

It is evident from these figures that by 2000, Europe had already lost the large tanker and bulk carrier business. But in other sectors, such as container ships, ferries and Ro-Ro ships, general cargo ships, chemical tankers, and of course above all, cruise ships, it still had a fair or even dominant share of the world merchant shipbuilding market.

We will see that in the early twenties of this century, the picture has become completely different. The Drewry report also mentions that around the year 2000, the major European engine builders enjoyed a 57 per cent share of the world market.

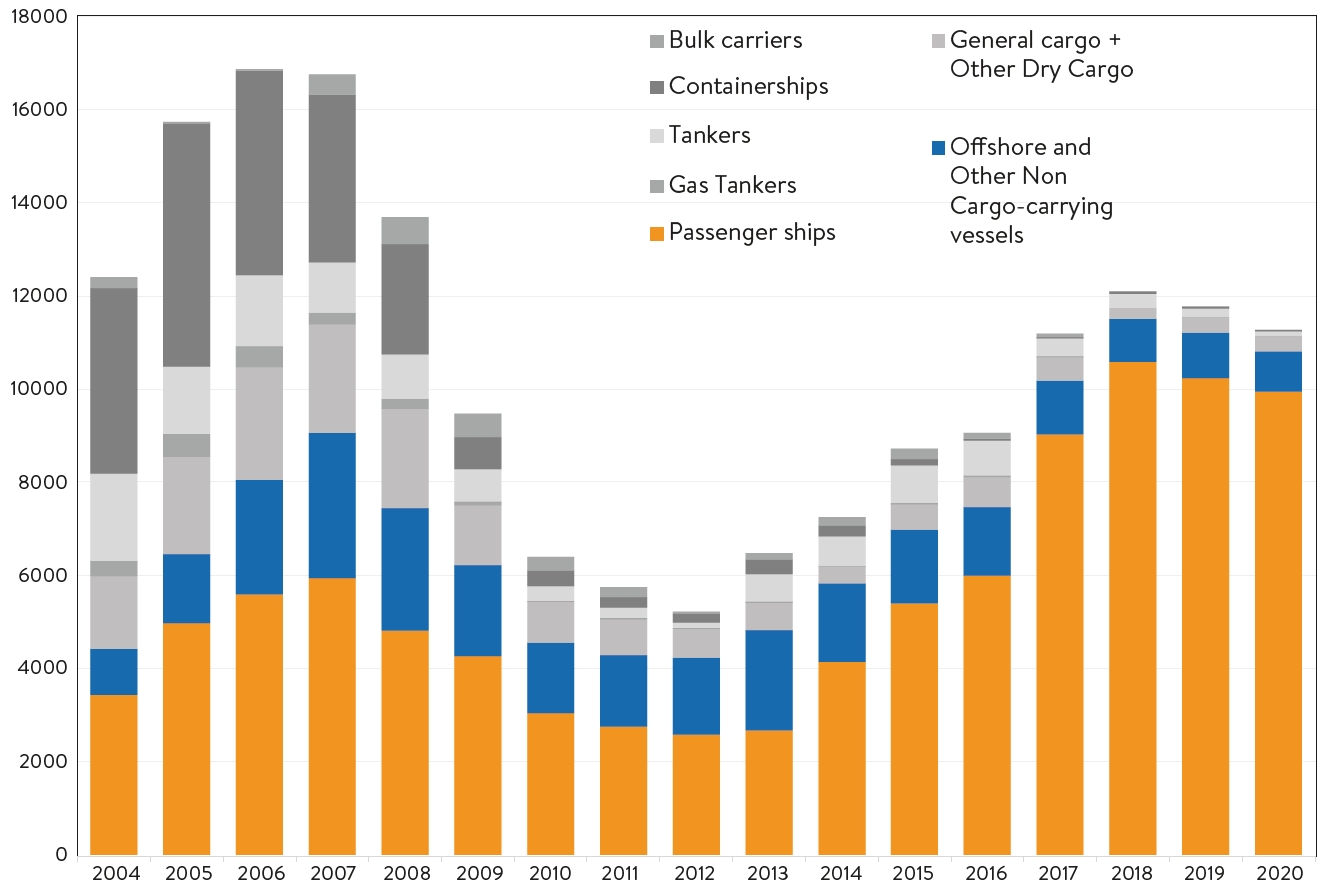

As the graph above shows, following 2000, the European share of the world’s commercial shipbuilding in Compensated Gross Tonnage (CGT) went gradually down from close to 25 to well below ten per cent of the world’s yearly shipbuilding production. In tonnage figures, between 2000 and 2010, European production was fairly constant, mostly well over 4 mCGT, but after 2010, production went down to below 2.5 mCGT in more recent years.

Also read: €2.3 million for Dutch Sustainable Shipbuilding Subsidy Scheme in 2023

Today’s order book

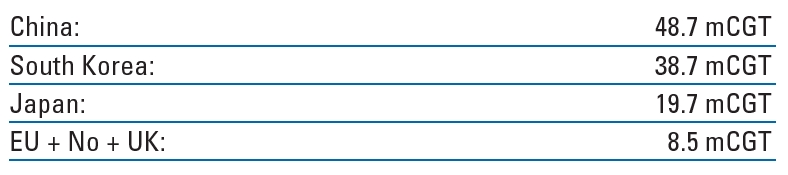

In spring 2023, the world order book in CGT looked about as follows:

The order books of the European countries consist mainly of old orders, placed a couple of years ago by cruise companies. According to Clarksons, in recent years, the European yards received only a very limited share of new contracts: six per cent in 2020, two per cent in 2021 and three per cent in 2022, all in CGT terms. The three EU countries with the largest order books are Italy, Germany and Finland. However, these are almost exclusively orders for cruise ships.

With the exception of the Netherlands, blessed with a number of contracts for general cargo ships and small tankers, none of the European countries have succeeded in obtaining contracts of any importance for cargo ships of any type or for larger Ro-Ro/passenger ferries.

The gradual evolution of the European order book’s product portfolio by ship types is shown in the figure below, taken from a SEA Europe report. The fate of European large commercial shipbuilding was perhaps sealed when in 2009 Maersk announced the closure of its Odense Shipyard, famous for building large container ships, tankers and bulk carriers. For our country, the delivery of the last large passenger ferry by Van der Giessen de Noord in 2003 seems a comparable moment.

Also read: European shipbuilding: Quo vadis? European Jones Act? A personal observation

Future is at stake

Some 75 per cent of European trade is carried in cargo ships; millions of passengers use the Baltic, Channel and Mediterranean ferries every year. The development shown above will cause that within a few years’ time, all this transport will be carried by means of container ships, tankers, ferries and all sorts of other cargo ships built at Asian yards.

Perhaps Europe should consider whether this is an acceptable situation, seen from a strategic viewpoint. The worries from the Secretary General of SEA Europe are understandable; the future of European large-scale shipbuilding is at stake. Our shipbuilding should not only be dependent on the building of cruise ships. How long will this continue, will we be able to keep the competition at bay? China has already entered this market and is increasing its order book in this field. This month saw the floating out of the Adora Magic City, the first large cruise ship built by a Chinese yard, a ship of 135,500 GT for more than 5000 passengers.

The above deals with merchant ships, seagoing and larger than 100 GT. There are other types of shipbuilding, for the offshore industry and inland shipping, yachts, fishing vessels, naval vessels, etc. Of great importance, certainly for our country, but small on a world scale.

In order to keep a viable maritime manufacturing industry, with all the facilities associated with such an industry, like education, research and development, knowledge centres, designers and equipment manufacturers, etc, Europe needs to also build ships other than small ones and cruise ships.

In its 2021-2022 annual report, the German Shipbuilders’ Association VSM refers in this respect to Strategische Autarkie: ‘Deutschland und die EU stehen in besonderer Verantwortung, um künftige Schiffbauprojekte zu ermöglichen.’ Hopefully, the EU and its member countries will respond to this cri de coeur.

Picture: Photo: The 173.85-metre ferry Mont St Michel belongs to Brittany Ferries. It was built between 2001 and 2002 at the Van der Giessen shipyard in Krimpen aan den IJssel, the Netherlands (by Raimond Spekking/CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons).

Also read: ‘There’s just ten years to go for shipbuilding in Europe’