Almost all marine sewage treatment plants have been type tested on land, but the majority of these do not meet the performance standard on ships. This may drive a wedge between between environmental goals and type approval regimes. Compliance monitoring may help solve the issue, says Wärtsilä.

In an article submitted to SWZ|Maritime, Dr Wei Chen, Future Program Development Manager at Wärtsilä Water Systems, Mark Beavis IEng IMarEng FIMarEST, Sales Director at ACO Marine and Oliver Jost, Maritime Environmental Affairs at the Wasserschutzpolizei (Water Police) in Germany discuss the shortcomings of sewage treatment plants (STPs) type tests. Read their full article below.

Many STPs do not even conform to the sewage treatment plant testing guidelines. Unacknowledged and uncorrected, these certified magic boxes and non-conformities have driven a wedge between the IMO’s environmental goal and the type approval regimes. To an industry that is accustomed only to type tests, to ‘confirm the lifetime performance of STPs’ (PPR 7/16)’ causes anxiety. Yet, few maritime professionals have wondered how on earth those science-defying magic boxes were “successfully” tested, approved and certified in the first place.

This sewage is not that sewage

Most type tests are carried out at municipal wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs). Some knowledge of WWTPs such as that illustrated by a recent BBC documentary “The Secret Science of Sewage” [7], is useful.

An STP needs to be tested for ten days, using fresh raw sewage with a minimum total suspended solids (TSS) concentration of 500 mg/l, by adding primary sewage sludge as necessary.

Domestic sewage, or urban wastewater, depicted in 6’00”-10’30” of the documentary, contains grey water from households, groundwater infiltration, and rainwater. Its average TSS is a mere 210 mg/l [8]. To meet the 500 mg/l criterium, primary sludge must be added.

If primary sludge is not added, the lab results would bear no relation to the test, and the test is clearly rigged. The tricks involved in such a rigged test could be revealed by an investigation. But there may never be one [6]. Who is to check the checkers?

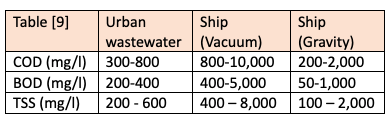

Nevertheless, 500 mg/l is only a fraction of that of a ship’s vacuum sewage (see table). One missing ingredient is grey water. Ship’s grey water should be regulated like that on land [10]. It can bring ship’s sewage closer to domestic sewage ashore. Introducing conditioning water can also help, provided STPs are not turned into dilution machines. In any case, to test an STP with one sewage, and use it for another sewage of much higher concentrations does not serve the maritime industry nor the IMO’s environmental goal.

Define primary sludge

Primary sewage sludge, depicted during 27’30”-29’30” of the documentary, is a black, smelly slurry with 30,000~50,000 mg TSS/l. The particles that have been settled from the raw sewage (photos) are the right material to create the challenging test conditions.

It should be noted that the primary settlement tanks of some WWTPs receive surplus activated sludge and produce a “co-settled sludge” that is less challenging than primary sludge and, therefore, unfit for type tests. Defining primary sludge is essential, but it is not enough.

The trick of using activated sludge

A trick harder to tell is when activated sludge is used in disguise as primary sludge. WWTPs serving our cities, towns and villages use biological treatment, or activated sludge process. Activated sludge is a brownish-coloured pollutant-destroying muddy water, with an earthy smell resembling that of garden compost (36’00”-40’50”). It contains naturally occurring aerobic bacteria and larger microorganisms such as protozoa (photo).

Treated effluent is readily separated out from this activated sludge by settlement, flotation, or membrane filtration. Hence, adding activated sludge to boost up TSS and organic content of STP influent can easily cheat a type test.

Likewise, when a physical-chemical STP produces a brownish-coloured sludge (photo below), the test may be rigged. Only with an STP influent suitably qualified, it can then be quantified for a valid type test to start.

Tougher type test can be shooting in the dark

Many other tricks exist. Residual chlorine may not be tested in-situ; coliform samples may not have its residual chlorine neutralised; flow meters may not be installed; STP sludge may not be prevented from entering the STP influent [4]. These tricks have led to magic boxes that are smaller, simpler, cheaper, “care-free”… and popular [2-6].

Introducing tougher tests seems logical. However, with these certified magic boxes and non-conformities unacknowledged, do we know how to make a type test tougher? For example, when a ten-day test failed to catch a magic no-sludge batch process that completes in an hour, extending the test to thirty days can be a pointless distraction from real improvements that matter, such as the need to define primary sludge, to investigate the root causes of the certified magic boxes and non-conformities, to ensure genuine lab results by rooting out fraudulence.

Without evidences, rationales, and justifications, introducing tougher type tests can be like shooting in the dark. Shooting in the dark merely makes existing tricks more attractive and encourages cleverer tricks.

ISO approved and independent facilities?

Have ISO17025-approved testing laboratories helped? Evidently not. For years, the EU’s Marine Equipment Directive (MED) has ensured that ‘testing laboratories used for conformity assessment purposes meet the requirements of standard EN ISO/IEC 17025:2005’. But this has not stopped magic boxes and non-conformities from being embellished with the prestigious wheel marks [2-6].

For decades, the Unites States Coast Guard has required ‘independent’ and ‘accepted’ facilities. But unfortunately, similar magic boxes and non-conformities have been wrongly approved [2,4-6], and the performance status of Type II Marine Sanitation Devices (MSDs) is as poor as that of STPs [11,12].

The way forward

Independent and approved facilities have merit, not least to ensure the basic conformities and seaworthiness of STPs. Tougher type tests can also have merit, when supported by rationales and evidences. But the reliance on type tests to serve the IMO’s environmental aspirations may only be supported when the certified science-defying magic boxes and non-conformities [2-6] are one day acknowledged for what they are, and correctly accordingly. The only question is, will this day ever come?

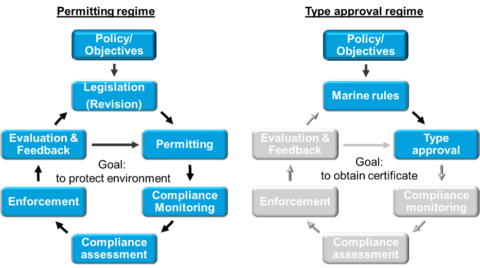

Type tests on board ships are more complicated and prone to tricks than those on land. There is only one way to protect the environment: compliance monitoring (see figure). It has been tried and tested by large Alaska-going cruise ships for twenty years, and by the rest of our society for much longer.

As alien as it may be, compliance monitoring may finally come to MARPOL Annex IV. Many proposed to sample an STP once every five years. Although it is a frequency unproven and unsupported by the effective regimes of the rest of our society, it could mark the start of a goal-based environmental regulation which would one day stop the magics of type tests from pulling the wool over our eyes.

References

[1] MEPC 71/INF.22, MEPC 74/14, PPR 8/7, PPR 7/16/1, PPR 8/7/4

[2] https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:6770412800591376384/

[3] https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:6757944192019816448/

[4] https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:6764478961243226112/

[5] https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:6761939034337017856/

[6] https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:6721362924335611904/

[7] The Secret Science of Sewage: https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/m000t8zl via @bbciplayer (accessed in June 2021).

[8] Wastewater Engineering, Treatment, and Reuse, 4th edition, by Metcalf&Eddy, 2003.

[9] Sewage discharge to port – what to expect, by Dr E Dorgeloh, and M. Joswig, SOWOS 9, 2015.

[10] https://www.maritime-executive.com/corporate/regulating-grey-water-a-necessity

[11] https://beta.regulations.gov/document/EPA-HQ-OW-2019-0482-0013