In 1978, the m.s. München (picture above) sent out a distress call after hitting severe weather. The Smit Rotterdam responded.

This article has been compiled by and submitted to SWZ|Maritime by Towingline-Hans van der Ster

Eternal Father, Strong to Save

"Eternal Father, Strong to Save" is a British hymn traditionally associated with seafarers, particularly in the maritime armed services. Written in 1860, its author William Whiting was inspired by the dangers of the sea described in Psalm 107.

It was popularised by the Royal Navy and the United States Navy in the late nineteenth century, and variations of it were soon adopted by many branches of the armed services in the United Kingdom and the United States. Services who have adapted the hymn include the Royal Marines, Royal Air Force, the British Army, the United States Coast Guard and the US Marine Corps, as well as many navies of the British Commonwealth.

Accordingly, it is known by many names, variously referred to as the Hymn of Her Majesty's Armed Forces, the Royal Navy Hymn, the United States Navy Hymn (or just The Navy Hymn), and sometimes by the last line of its first verse, "For Those in Peril on the Sea".

The hymn has a long tradition in civilian maritime contexts as well, being regularly invoked by ship's chaplains and sung during services on ocean crossings.

The Storm on the Sea of Galilee is a painting from 1633 by the Dutch Golden Age painter Rembrandt van Rijn.

The Storm on the Sea of Galilee is a painting from 1633 by the Dutch Golden Age painter Rembrandt van Rijn.

Some went out on the sea in ships; they were merchants on the mighty waters.

They saw the works of the Lord, his wonderful deeds in the deep.

For he spoke and stirred up a tempest that lifted high the waves.

They mounted up to the heavens and went down to the depths; in their peril their courage melted away.

Eternal Father, strong to save,

Whose arm hath bound the restless wave,

Who bidd'st the mighty ocean deep

Its own appointed limits keep;

Oh, hear us when we cry to Thee,

For those in peril on the sea!

Rig Towage to Marseille

The ocean-going tug Smit Rotterdam with its 22.000 horsepower departed from Rotterdam in October 1978 and connected up a Jack-up rig in the North Sea bound for Marseille. With on board the famous maritime cineaste Pim Korver to make a movie of the Smit Rotterdam and its crew just to show the difference after the movie of Hollands Glorie.

The weather was fair and the tug made a good speed and within three weeks’ time, it delivered the jack-up rig to the client in Marseille. The Smit Rotterdam continue its voyage to Barcelona to change its captain and dropping off Mr. Pim Korver.

Santa María

In the port of Barcelona, was seen the replica of the Santa María. The Santa María was the flagship and supply ship of Christopher Columbus, who in 1492 'discovered' America . However, he was not the first European to set foot there, that was a Viking from the ship of Leif Eriksson, who came from Greenland, probably in 1001 or 1002. The ship of Columbus was originally called María Galante, but since this was also synonymous with a prostitute, it was decided to change the name.

The replica of the Santa María at Barcelona.

The replica of the Santa María at Barcelona.

On the Christmas night of 1492, the Santa María suffered shipwreck off the coast of Quisqueya, later called Hispaniola. It was very shocking to see such a small ship compared with the big and strong Smit Rotterdam and difficult to understand that they have some 100 sailors on board while the Smit Rotterdam sailed with 18 persons only. After the Smit Rotterdam was cleared from Barcelona, it set sail to Horta on the Azores island Faial to take up its station duties during the winter months.

Station Duties Azores

Horta is a single municipality and city in the western part of the Archipelago of the Azores, encompassing the island of Faial. In 1921, Dutch seagoing tugboats began to use Horta as salvage station for the North Atlantic shipping crossings. After World War II, they returned during the period of European reconstruction.

The Smit Rotterdam anchored in the marina bay with for the Smit crew a daily view on the well-known Café Sport. A period of waiting for the crew of the Smit Rotterdam started. The normal works of maintenance with special radio listening of the North Atlantic traffic and salvage equipment testing. And so the worst winter station of December 1978 started.

The Port of Horta on the island Faial, one of the Portuguese Azores in the North Atlantic.

S.O.S. Greek Cargo Vessel

On the 10th of December, the radio officer of the Smit Rotterdam received a mayday call from a Greek vessel in distress in the Gulf of Breton. It reported that the shaft sealing was leaking and it was flooded with water. The Smit Rotterdam anchored up and with full power, it sailed to the given position. The weather was very bad, strong winds with 10 to 11 hurricane force.

After more than 12 hours of sailing, the Greek vessel reported that it had everything under control and could continue its voyage. The Dutch ocean-going salvage tug Smit Rotterdam returned to the salvage station.

In the meantime, it received a telex that the München had sent out a mayday and the search for the München began.

Smit Rotterdam Directed Search for the München

Smit Rotterdam.

On 12 December 1978, the Smit Rotterdam, which was off the Azores at the time, received a telex from the listening service with the information that the German containership München, had sent out a mayday signal. In a severe storm gusting to force 10, the Smit Rotterdam with captain P. de Nijs in command, sped to the position given.

The Smit Rotterdam shipped heavy seas, which battered it and even caused damage to one of the working boats, but the ocean going tug fought its way through the raging water. From search- and rescue planes the Smit Rotterdam received only negative reports. Not a trace was to be found of the München in the area in question and no further distress signals was received. The Smit Rotterdam crew realised that the situation was critical.

Captain P. de Nijs at the chart table.

Sitting by the Radio

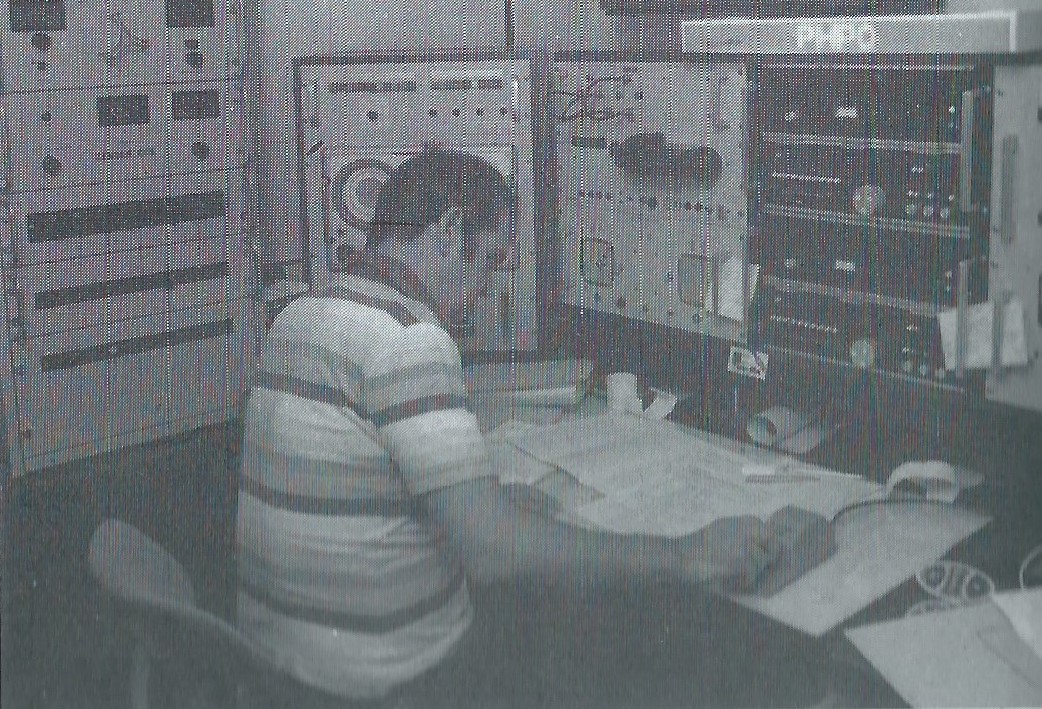

The radio-station served as a communications and crisis centre. Radio-officer Ronnie Verschoor constantly sent out appeals to all vessels in the neighbourhood to report, while captain De Nijs plotted all their positions on the map. The mate had posted double look-outs on the wings with all crew members available, whilst the remaining crew members got the remaining workboat, the inflatable Zodiac, the hospital, diving gear, tools and numerous lines and wires ready.

During the following ten days of radio silence, so as to be able to hear any distress signals, captain De Nijs and radio-officer Verschoor hardly ever left the radio station. All reports and further particulars from the searching ships and aircraft were channelled to this communications centre.

Section by Section

A search pattern had been set out on the sea chart, and all ships movements were continually updated on the plotting table. For days on end, some 14 ships in line with the Smit Rotterdam at about 4 miles distance from one another searched the map sections. On reaching the end of each section the whole convoy pivoted round the Smit Rotterdam to begin searching the next section.

Radio-officer R. Verschoor at the radio station.

110 Vessels and 16 Planes

In view of the fact that the search area was in the centre of the transatlantic shipping route, a total number of 110 vessels participated in the search. The 16 search and rescue planes were also controlled from the Smit Rotterdam and on the basis of the findings they reported, ships were directed to the supposed floating objects.

Unfortunately, it turned out to be a false alarm in most cases. Only fishing gear, oil slicks, or garbage were found. Ultimately, only three lash-barges were found after one sank later on. The other two were eventually towed to Lisbon by the Smit Rotterdam and the German tug Titan respectively.

First Time an Ocean-going Tug Directs a Search This Size

It was the first time in history that an ocean-going tug directed such a unique search of that size. Notwithstanding all the efforts and the vast amount of work carried out by the crew of the Smit Rotterdam, the outcome was regrettably negative. The loss of the München is likely to remain a mystery for ever. Captain, officers and the other members of the crew of the Smit Rotterdam received messages of thanks and appreciation for the professional way in which they handled the search from the Hapag-Lloyd shipping company and from Land's End coastguard.

m.s. München

The m.s. München was a German LASH carrier of the Hapag-Lloyd line that sank with all hands for unknown reasons in a severe storm in December 1978. The most accepted theory is that one or more rogue waves hit the München and damaged it, so that it drifted for 33 hours with a list of 50 degrees without electricity or propulsion.

Early Career

The München was launched on 12 May 1972 at the shipyard of Cockerill, Hoboken, Belgium and delivered on 22 September 1972. The München was a LASH ship and was the only ship of its kind under the German flag. It departed on its maiden voyage to the United States on October 19, 1972.

Its sister ship, the m.s. Bilderdijk was built for the Holland America Line at the Boelwerf Temse Shipyard, also in Flanders, Belgium (yard number 859). It sailed under the Dutch flag until 1986 when it was renamed Rhine Forest. This ship was retired from commercial operation on 15 December 2007. It was then scrapped in Bangladesh.

Lash carrier Rhine Forest in 2006 in the Waalhaven of Rotterdam; the Netherlands.

Last Voyage and Search Operations

The München departed the port of Bremerhaven on 7 December 1978, bound for Savannah, Georgia. This was its usual route, and it carried a cargo of steel products stored in 83 lighters and a crew of 28. It also carried a replacement nuclear reactor-vessel head for Combustion Engineering, Inc.

This was its 62nd voyage, and took it across the North Atlantic, where a fierce storm had been raging since November. The München had been designed to cope with such conditions, and carried on with its voyage. The exceptional flotation capabilities of the LASH carriers meant that it was widely regarded as being practically unsinkable.

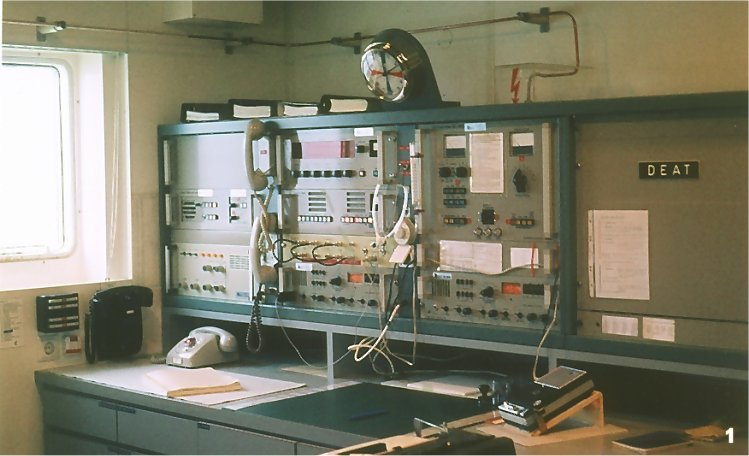

Radio station of the München with call sign “DEAT”.

The München was presumed to be proceeding smoothly, until the night of 12/13 December. Between 00:05 and 00:07 (all times GMT) München's radio officer Jörg Ernst was overheard during a short radio communication on a "chat" frequency. He reported bad weather and some damage to the München to his colleague Heinz Löhmann aboard the m.s. Caribe, a German cruise ship 2400 nautical miles (4440 km) away. Ernst also transmitted München's last known position as 44°N 24°W.

The quality of the transmission was bad, so that not everything was understood by Löhmann. Since it was a standard communication, the information was not relayed back to the ship's owner until 17 December.

Distress Call

Around three hours later (03:10-03:20), SOS calls were received by the Greek Panamax freighter Marion, which relayed it to the Soviet freighter Marya Yermolova and the German tug boat Titan. M.s. München gave its position as 46°15′N 27°30′W, which was probably around 100 nautical miles (200 km) off its real position.

The Greek Panamax freighter Marion received the SOS calls from the München.

The messages were transmitted via morse code and only parts of them were received. One fragment received was 50 degrees starboard, which could be interpreted as a 50-degree list to starboard. Automatic emergency signals were also received by multiple radio stations starting at 04:43. No further calls were recorded after 07:34, probably because US stations stopped listening on the frequency 2182 kHz.

At 17:30 international search and rescue operations were initiated and co-ordinated throughout by HM Coastguard at Land's End, Cornwall. Wind speeds of 11-12 Beaufort were reported in the area of the search, hampering efforts. The initial search requested by HMCG was by RAF Nimrod maritime recognisance aircraft. This air asset was co-ordinated by SRCC RAF Mountbatten.

Initial Search Efforts and Further Communications

The next day, 13 December, an additional C130 Hercules aircraft from Germany and six ships searched for the München. At 09:06 Michael F. Sinnot, a Belgian radio amateur in Brussels, received a voice transmission on the unusual frequency 8238.4 kHz, which is usually used by the German ground station Norddeich Radio. The transmission was clear, but interrupted by some noise, and contained fragments of München's name and callsign. Later in court, Sinnot reported that the voice was calm and spoke in English, but with a distinct German accent. Since Sinnot only had a receiver for this frequency, he relayed the message via telex to a radio station in Ostend.

A C130 Hercules joins the search.

A C130 Hercules joins the search.

Between 17:00 and 19:14, ten weak mayday calls were received by the US Naval Station Rota, Spain, at regular intervals, mentioning "28 persons on board". The messages may have been recorded and sent automatically. The München's call sign, “DEAT” which was sent in Morse code, was received three times on the same frequency.

The Dutch ocean-going salvage tug Smit Rotterdam, which was returning from other mayday calls in the Gulf of Breton and the English Channel, received the calls as well and went to the designated position under the command of Captain P.F. de Nijs. Seas were heavy, with a swell averaging 22 metres. Land’s End CG provided the search planning and areas to be covered and appointed the salvage tug Smit Rotterdam as On scene Commander co-ordinating the activities of eventually more than 100 ships and also the 16 aircraft taking based all now temporarily based in the Azores.

The Search Intensifies

On 14 December, wind speeds dropped to Force 9. By now 4 aircraft and 17 ships were participating in the search operation. Signals of the München's emergency buoy were received. At 19:00, the British freighter King George picked up an empty life raft at 44°22′N 24°00′W. The same day, Hapag-Lloyd's freighter Erlangen found and identified three of the München's lighters.

The following day, 15 December, a British Hawker Siddeley Nimrod patrol aircraft discovered two orange objects shaped like buoys at 44°48′N 24°12′W and the salvage tug Titan recovered a second life raft. A third one was located at 44°48′N 22°49′W the next day by m.s. Badenstein; all were empty. A yellow barrel was also sighted that day.

On 17 December, at 13:00, the Düsseldorf Express salvaged the München's emergency buoy. By now wind speeds dropped to Force 3. The freighter Starlight found two life belts, at 43°25′N 22°34′W the Sealand Consumer picked up a fourth empty life raft. Three life vests were also sighted, two of them by the Starlight and another one by the Evelyn.

The Search Is Called off

The international search operation officially ended in the evening of 20 December, a week after it had begun. The West German government and Hapag-Lloyd decided to search for two more days, with British and American forces supporting them. The search effort had been the largest undertaken to that date.

Altogether, 13 aircraft from the United Kingdom, the United States of America, Portugal and Germany, and nearly 80 merchant and naval ships had searched for the München or its crew. On 16 February, the car transporter Don Carlos salvaged a lifeboat from the starboard side of the München, the last object discovered from it.

First Investigation Points to Severe Weather

The subsequent investigation into the disappearance of the München centred on the starboard lifeboat and in particular the forward block from which it had hung. The pins, which should have hung vertically, had been bent back from forward to aft, indicating the lifeboat hanging below it had been struck by a huge force, that had run from fore to aft of the ship, and had torn the lifeboat from its pins. The lifeboat normally hung 20 metres above the waterline.

With the existence of rogue waves then considered so statistically unlikely as to be near impossible, the investigation finally concluded that the severe weather had somehow created an “unusual event” that had led to the sinking of the München.

Rogue Waves Real

As the science behind rogue waves was explored and more fully understood, it was accepted that not only did they exist, but that it was possible that they could occur in the deep ocean, such as in the North Atlantic. Investigators later returned to the question of the München and considered the possibility that it had encountered a rogue wave in the storm that night.

Whilst ploughing through the storm on the night of 12 December, it was suddenly faced with a wall of water, between 80 and 100 feet (24 to 30 metres) high, looming out of the dark. The München would have plunged into the trough of the huge wave, and before it could rise out of it, it collapsed onto it, breaking across its bow and superstructure, tearing the starboard lifeboat out of its pins and likely smashing into the bridge, breaking the windows and flooding it.

Having lost its bridge and steering, it would probably have lost its engines. Unable to maintain its heading into the storm, it would have been forced broadside into the waves. It seems to have floated for a number of hours, during which the storm and inaccurate positioning prevented it from being located. The force of the waves then hulled or even capsized it; another rogue wave may have contributed to its distress. It would then have succumbed to the flooding and sunk within a short period.

Report from One Person on Board a Searching Vessel

‘It is the night of the 11/12 December. Over the North Atlantic a heavy hurricane had been raging for days. The mean wave height, according to predictions and measurements, is more than 16 meters. Massive volumes of water have begun to move in the north-west storm, the sea is boiling, the wind is screaming.

Massive volumes of water are moving.

In the middle of it, a large LASH carrier heads for the American East Coast, powered by a state-of-the-art 26,000-horsepower machine capable of driving 18 knots. The huge ship is five days behind Bremerhaven, far out in the Atlantic, a good 830 km north of the Azores and 1700 km behind Lizzard, the exit from the English Channel.

With a length of 240 metres and 37,000 GRT, it is significantly larger than the Titanic and, with state-of-the-art technology of its time, represents the pride of German maritime shipping. It has loaded "heavy stuff", machine and steel components into their self-floating barges, stacked in a double position, occupying the entire length of the ship behind the bodywork. Its name is München.

In the late evening, shortly after midnight, the radio operator of the large ship still has contact with the German passenger ship MV Caribe several thousand kilometres away on the Sabbelwelle. He reports of very bad weather and – as a result – damage to the structure, but speaks neither of imminent danger or even distress. After contact, the ship will probably continue its course through night and storm.

Just a few hours later, at 03.10 h, two ships on the Atlantic take on an electrifying paging: ‘SOS SOS SOS DEAT DEAT DEAT’ and a mutilated position message. This is the international call sign of the German cargo ship. The call will be routed as usual, with several ships in range immediately changing their course and heading for the distressed vessel's reported location, not a safe haven in prevailing weather conditions. The shipping company is notified, and in turn makes contact with the families of the sailors.

Early in the morning, a first Nimrod long-range reconnaissance aircraft sets off from England and flies out into the storm, finding weather conditions with west winds from 11 to 12 Beaufort arriving hours later in the target area. Calls to the München remain unanswered, the aircraft cannot find anything in the reported position. Slowly, it gets scary. Such a powerful ship cannot just disappear.

In the afternoon, the Dutch salvage tug Smit Rotterdam takes over the coordination on-site at sea and probably the largest search operation of German maritime shipping begins. More and more ships hurry on the busy North Atlantic route, are divided and search an area that is five times the size of today's Federal Republic over the next few days.

The German Navy relocates the Breguet sea ice reconnaissance aircraft from Northern Wood to southern England, later to the Azores, which then flies search missions non-stop. British, Portuguese and American machines are also in use. In the end, there are 75 ships and 13 planes on the way and find … nothing.

In the Azores, on the evening of 13 December, it is said that two hours of slower calls for help from the München were intercepted. On the morning of the 14th, the München EPIRB buoy begins to automatically send the vessel identification, a sure sign that it has floated out of its cradle at one of the highest points on the ship. Freezing cold is spreading in the radio network. Everyone who hears about it knows the meaning. Slowly, in the course of the following day, it becomes clear you may have been searching 350 km too far south due to an incorrect position. In the new search area, relatively fast driving barges, the radio buoy, life jackets and unopened life rafts in a thick layer of oil are found. No crew. Neither alive nor dead.

The search will continue. With high expenditure on ships, airplanes and humans. On 20 December, the international search was stopped. The shipping company in Hamburg did not want to give up and continued to search with its own ships. It was supported by German, American and English aircraft. On 22 December, they also had to stop the search. The München and its 28-member crew remain missing.

Green Water

The world is puzzling. How could such a thing happen? What had gone so horribly wrong that such a "super ship" and with it 28 people just disappeared almost without a trace in the depths?

As one of the innumerable possibilities, experts assume "green water" on deck, that is, the impact of an unbroken wave on the deck or on the bodywork. Trials in the towing tank later revealed clues to this thesis. For the damages also speak on the retaining bolts of the found lifeboat. In professional circles, this is called a sea beating and – depending on the amount of water – can have disastrous consequences for the integrity of the ship's hull. Years later, this is what happened to the only identical sister ship of the München, the Dutch Bilderdijk, in a storm. It just got away from it.

However, at the time (1978), such huge waves were considered impossible by definition of science and its "linear model" of wave development. Among seamen, however, there have always been rumours of "monster waves", "Kaventsmännern" or "Freakwaves". Those monstrous, all-destroying mountains of water, which seemed to come from nothing and are so much bigger, higher and more powerful than anything around them. But no one admitted this out loud, certainly not a helmsman or captain who wanted to keep his patent and did not want to be suspended for drunkenness in the service.

17 years after the München, the Norwegian oil drilling platform Draupner-E was unequivocally documented during a storm in the North Sea in which a single 26 m high wave was measured. A rethinking began. Today, you do not just know that they exist, but also that such monsters are much more common than assumed. There even seem to be "hotspots" for them and they are obviously still much higher than the Draupner wave; 35 m cannot be ruled out.

Ultimately, the reason for the downfall of the München cannot be clarified. Most likely, a chain of events that may have started with a sea beating. It is equally certain that the ship stayed afloat for many hours, possibly until the morning of 14 December, just as the buoy began to swell and send. After a careful examination of the few pieces of evidence, the Maritime Inspectorate later made little statement: ‘… an extraordinary event must have occurred due to bad weather, causing the sinking of the ship.’ It lies in the dark depths of the North Atlantic as the grave of its occupation north of the Azores, somewhere on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, close to its last reported position at 46.15 N 27.30 W. There, the sea is 1000 to 4000 metres deep and any search would probably be in vain. And for what?

The World Grieves

What I have to do with it? I had been aboard my training ship since the summer of 1978, and we were at sea at the time of the search, albeit in a distant part of the world. Nevertheless, we followed everything, the listening radio operator gave out a Bulletin on how it stood with the search every few hours. After the first few hours of no success, the mood became ever more depressed – everyone on board knew how small the chance for the colleagues on board was.

And I myself could not imagine it – after all, I had been standing in the Bremerhaven at the Kaiserschleuse in the spring of that year and admired the huge ship that was on its way to the North Sea. Unimaginable that something so enormous could be brought to an end anywhere! When the search was stopped, there was silence on board. Everyone knew he could have been in the place of the sailors concerned. Christmas Eve we were in Santos on the South American coast and I celebrated Christmas in the local sailor club. In the devotion, as in the preselected speech of the Federal President, the team of the München was mentioned. It was depressing.

On 3 January 1979, there was a memorial service for the crew in the Bremen Cathedral. 2000 people came and Hamburg and Bremen were half flagged. The ceremony was broadcast, the Bremen taxis were wearing a mourning fleur. At the end of the moving service, the names of the 27 crew members and the travelling woman of one of the helmsmen were read out.

At the end of the service, 8 glasses sounded through the cathedral: Watching.

Towing Lash Barges to Lisbon

On 22 December, the search to the München was stopped. Everybody on board the Smit Rotterdam was impressed and felt that this tragedy had a very heavy impact on their lives, but there was no time to think about it. Work continues and the search for the floating Lash container asked their attention.

Floating Lash container.

Just after a half day, the Lash container was found. The problem for the crew of the Smit Rotterdam was how to connect this Lash container for towage. Its very heavy 9 inch towing wire was useless for the job. The weight of the towing wire is so big that when connected, the towing wire would pull the Lash-barge down and sink it. However, a connection was made with a smaller towing wire which connected the Lash-barge to the Smit Rotterdam’s wire storage reel.

After the connection was made, the Smit Rotterdam slowly towed the Lash-barge to Lisbon. The weather was much better, but the sea remained bad with high waves. On the 26 December, the tug arrived on the Lisbon roads, but if you think that all was clear and fine for the crew, that is a mistake.

During the handover of the Lash-barge to the local tugs. Strong wind gusting with heavy rain overtook the transport. Yet, the experienced crew succeeded in transferring the Lash-Barge to the harbour tugs and moored the barge safely at a berthing place. The Smit Rotterdam also moored safely to a berthing place. The engines were stopped and the full crew could relax for the first time after three weeks of intensive duties.

Station Duties

After delivering the Lash barge, the Smit Rotterdam set sail to southwest Portugal for station duties. It dropped anchor on the 29 December in the Bay of Lagos. It is good to give crew some rest after the efforts and experiences of the past 2.5 weeks. However, much rest to the crew was not given.

The Smit Rotterdam received orders from the head office in Rotterdam to pick up its Azoren station sailing with economic speed. In the morning of the last day of the year, the anchor was heaved up and the Smit Rotterdam sailed from the Lagos Bay bound for Horta.

Around 21.00 hrs the same day, the crew, free from watch, notice that the engines of the Smit Rotterdam start running on full power. A few minutes later, the Captain enters the messroom with the message that there is a tanker in distress and that the Smit Rotterdam is underway at full speed.

Getafix

The tanker, the 46,827‐ton Dutch‐owned, Liberia‐registered Getafix, was in trouble with a flooded engine room 95 miles north‐northwest of Lisbon. ‘It was stopped dead in the water,’ the duty officer reported. It was not immediately known what, if any, cargo it had or how many crewmen were aboard. The weather was reported as poor.

In the morning of New Year’s day 1979, the tanker was reached and with a black out and rolling heavily in the North Atlantic swell. The life/workboat was making ready with salvage equipment, pumps and generator sets. The engine room had flooded, but it was reported that with the seawater inlet valves closed, the flooding had stopped.

The workboat reached the Getafix and dropped the salvage equipment on board. The second engineer of the Smit Rotterdam jumped on board to start up the pumps to dry the engine room and the emergency towing connection.

The Getafix.

The radio officer of the Getafix describes the tanker’s voyage of the tanker below after he signed on in Rotterdam till the Getafix was safely delivered in Rotterdam.

A Trip to Remember

After 40 years, it is time to put my memories on paper. Mid May 1978 I joined the Liberian flagged tanker Getafix as a 20 year old radio-officer in Europort – Rotterdam, not realizing how it would end.

The Getafix was a tanker of 102.065 tons dwt, built in Norway as Credo. In 1976, it was transferred to Liberian flag. Technical and crewing management was put in the hands of Nievelt, Goudriaan & Co, at the time a well-known Dutch shipping company based in Rotterdam.

From Rotterdam, we departed for Teesport, U.K., to load Northsea-crude for Freeport Bahamas. Upon completion of discharging, we were ordered to proceed to the Mediterranean, with a prospective trip to the Gulf of Mexico. Eventually we loaded in Arzew, Algeria, and Ras es Sider in Libya. While passing off Malta, a technician came out by a small tug with a Loran navigator. This was necessary to comply with US rules and regulations on navigation equipment. In the Gulf of Mexico, the greater part of the cargo was ship-to-ship transferred to another tanker while the remainder was discharged in Houston.

From Houston, there was an 8-week voyage to Singapore where a drydocking was planned. During this 8 week trip, preparations were carried out, such as tank-cleaning. The drydock took place for about 6 weeks at the Sembawang shipyard in the north part of Singapore.

Two Norwegian class surveyors were in charge of the surveying of this drydock period. The Getafix was originally Norwegian and classed by DNV. After the drydock, a voyage from Indonesia to West Europe was planned. Unfortunately, the drydock period did not deliver much benefits, we were regularly plagued by black-outs and such. Quite annoying when you are awaiting your turn with Scheveningen Radio to obtain or send your Radio traffic.

Emergency Repairs Cancelled

At a certain moment, a more serious problem developed in the engine-room. In consultation with Nievelt (Nigoco) it was decided to carry out emergency repairs in Capetown. However, a few days before arriving at Capetown, we received a telegram from Nigoco that the emergency repairs were cancelled because of economic reasons. The engineers were not very pleased by this decision, to put it mildly. So we kept soldiering on towards Rotterdam.

A Real Problem Occurs

Unfortunately on 31 December 1978, we encountered a real problem. A main coolwater pipe burst and the engine-room flooded, resulting in a dead (the lights o/b flickered a couple of times, but we were all already used to that).

'Call Your Friends'

The chief officer appeared suddenly in the radio room, saying the legendary words : ‘Sparks, I think it is now time to call your friends.’ (I have always been and still am a tug-lover, which can be easily explained by the fact I grew up in Maassluis, homeport of the Smit tugs.

I did send a XXX message requiring tug assistance, we were dead ship. The call was acknowledged and relayed by Monsanto radio/CUL. A Russian vessel with callsign URIL also responded. After a short while, the tug Smit Rotterdam offered assistance and gave an ETA of early morning 1 January. The German tug Titan also offered assistance, but because of our Dutch background, the Smit Rotterdam was accepted.

Despite a heavy swell still running, the Smit Rotterdam succeeded in transferring small generators and pumps o/b Getafix. Second engineer Hans van der Ster also managed to get o/b Getafix. An emergency towing connection was made (easier said than done on a dead ship) and course was set for Vigo, Spain.

After a 3 day towing trip, we entered the Bay of Vigo. The towing line was disconnected and the Smit Rotterdam came alongside to provide electricity, et cetera. As our galley was dead as well, we endured 3 days of compulsory cold buffet. The complete crew of Getafix was therefore invited for a good hot meal on board the Smit Rotterdam. It was nice to see on the noteboard of Smit Rotterdam: “o/b the casualty NO SMOKING”.

Arrangements were made to get a more powerful generator from the Holland o/b Getafix in order to provide energy to keep the cargo of 96.000 ton Indonesian crude at the correct temperature. A proper towing connecting was also set up for the trip to Rotterdam.

In the meantime, two (rather nervous) company superintendents arrived o/b. There were a few spare seats in their charter plane, so some of the officers left the vessel, stating: ‘I will not sail another mile with this derelict floating oil tin, certainly not without a radio-officer.’

In the end, I was asked whether I was willing to stay o/b during the towing trip to Rotterdam. I agreed, being a tug-lover, but this time on the other end of the tow-line. I did the 3rd officer’s navigational watch and radio communications in between. Navigation also had my interest and putting Decca positions on the chart does not require a genius.

Shortly after departure from Vigo, the weather was very nice and we made a speed of about 8 knots, but as soon as we entered the Bay of Biscay, the weather deteriorated fast. Speed reduced to 2 knots, the vessel was rolling heavily and there was lots of water on deck.

Upon approaching the entrance of the English Channel, the French navy provided escort services with a standby tug. Despite regularly transmitted navigational warnings, because Getafix was sheering behind the Smit Rotterdam, from some ship pretty close by. I frequently used the Aldis-lamp sending the letter D.

In the end, in consultation with the watch-keeping officer on the Smit Rotterdam it was decided to switch on part of our deck-light. It is a fact that a lot of light on a pitch dark sea, scares most of the other ships away. On the early morning of 15 January we arrived at Rotterdam. Between the breakwaters the Smit Rotterdam disconnected and with the assistance of 4 harbour tugs we were safely berthed.

My brother and father travelled to Hook of Holland, despite very wintry conditions and icy roads to see us enter port and take some photos. Another fact which still surprises me today, is that my brother had to read in a newspaper we encountered problems during new year’s eve. My father phoned the ship office, and Radio Holland. The content of this conversation is not suitable to put in writing here. Fact remains both were not able (or willing) to supply information.

These memories are strictly personal and any accusation towards Nigoco are on my account. The message with the cancellation of emergency repairs for economic reasons is very real. Nowadays, a trade union or crew would most probably prosecute the shipping company, or Port State detention would have been very likely. I certainly do not regret that Nievelt in the end ceased to exist as a shipping company.

Henk Ros, radio officer Getafix / 5LPC

Andros Patria

On the same day as the troubled Getafix, another tanker faced problems in the North Atlantic at the Spanish coast near La Coruna. The Andros Patria was a Greek oil tanker, which suffered a fire on 31 December 1978 northwest of Spain, resulting in about 50,000 tons of oil leaking into the ocean. Two Dutch ocean-going tugs were alerted and proceeded to the given location. The tugs Typhoon from Wijsmuller at IJmuiden and the Poolzee from Smit International at Rotterdam.

Off the north west coast of Spain, the Greek tanker Andros Patria caught fire. The explosion occurred midships and the captain, fearing that the entire ship would explode, ordered the lifeboats to be launched. Almost the entire crew along with the captain abandoned the burning tanker. Only the chief engineer and one crewman stayed aboard.

The fire did not spread and the chief managed to restart the engines, set the autohelm to avoid the coast, thus saving the ship and a greater environmental disaster. The tanker was carrying over 200,000 tons of Iranian crude oil and ultimately released over 14,000,000 gallons into the Bay of Biscay.

The ship was later taken in tow and salvaged. The lifeboat carrying the captain and the 33 crewmen who abandoned the ship, capsized in the heavy seas and all were drowned.

The Accident

In December 1978, the tanker Andros Patria of the United Shipping & Trading Company of Greece from Piraeus was on a journey with 208,000 tons of crude Iraqi heavy crude from Kharg to Rotterdam. At 6:20 pm on 31 December, the ship developed a crack in the outer skin through which oil spilled out in bad weather off Cape Finisterre. About two hours later, an explosion occurred at the cracked tank 3 of the ship, which set fire to the expiring oil cargo of the ship.

The ship initially requested that the crew be taken off board by a helicopter, but 34 of the 37 people on board, including the captain, his wife and 2 year old son, left the ship soon after with a lifeboat. The boat capsized in the heavy sea, killing all. The remaining three people on board were rescued by helicopter one day later.

On 4 January 1979, a salvage team boarded the ship and the Havarist was later taken in tow. Because Spain, Portugal, France and Great Britain refused to let the Havarist sail through their territorial waters, the Andros Partia was towed to the sea area south of the Azores and remaining cargo was lightened until 9 February 1979 at sea. After that, Portugal allowed the now empty tanker to be brought to Lisbon. Arriving in Lisbon, the insurers declared the ship to be a constructive total loss. The Andros Patria was sold for demolition and scrapped from 19 June 1979 in Barcelona.

Note: The Smit Rotterdam was the last tug that stayed as a salvage tug on station Azores. After this terrible winter, the company decided to leave the station. The decision was taken for economic reasons. The cost to have big ocean going tugs on station are much higher than the profit paid by the insurers.

After 57 years(1921-1978), the salvage station Azoren came to an end. However, the salvage company still exists and operates under the name Smit Salvage and is a part of Royal Boskalis. Salvages are carried out in a different way today. Tugs are hired and salvage material held standby at various strategic locations around the world.

ISU president Charo Coll said: ‘We need to accept the reality of different ways of working. The shipping and insurance industries must, in their own interest, recognise the need to provide sufficient remuneration to encourage investment in vessels, equipment, training and the development of highly qualified staff in order to continue to provide an essential global emergency response capability.’

Sources

- Sleeptros February 1979

- Wikipedia

- Seefunknetz

- Memories of Harm Jongman, chief officer of the Smit Rotterdam

- Memories of Hans van der Ster (towingline), second Engineer of the Smit Rotterdam

- Memories of Henk Ros, Radio Officer of the Getafix

- Timmscorner: reports from a searching vessel

- Photo Andros Patria

- Martyn Wingrove