Even when you comply with the rules, fatigue can still jeopardise safe operations on board a ship. In a recent Mars Report, the officer of the watch fell asleep due to fatigue resulting in his ship grounding.

The incident was covered in a recent Mars Report. These reports are compiled (anonymously) by The Nautical Institute to prevent other accidents from happening. A summary of this incident:

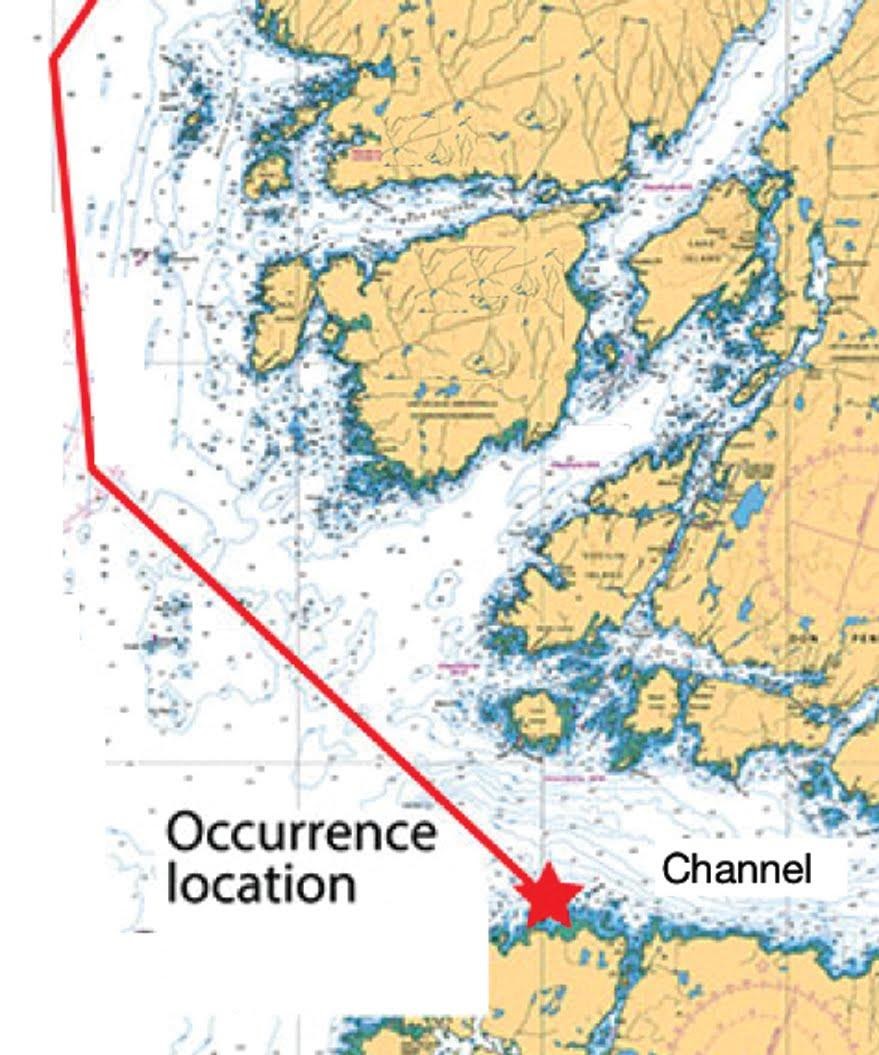

A tug was pushing a barge in ballast. The tug was connected to the barge with pins; an arrangement commonly called an articulated tug barge (ATB). At one point, the officer of the watch (OOW) altered the ATB’s course to port to pass one nautical mile off an island at the entrance to a channel.

Just over thirty minutes later, the ATB passed the next port alteration waypoint off the island, but did not alter course. At this time, the weather was light winds and rain, and a 0.3-metre sea.

Another crew member who was doing rounds called the OOW from the galley intercom radio, but received no response. After a second attempt, again with no response, he made his way to the bridge. A few minutes later, while he was still on his way to the bridge, the ATB struck a known and charted reef at the entrance to the channel. Following the impact, the OOW reversed both engines and placed the rudders hard to port.

The noise of the engine in full reverse and/or the vibration of the tug alerted the remaining crew. The master went to the upper wheelhouse, took over the watch, and instructed the OOW to ensure that the crew were awake and that they should survey the damage to the ATB.

The tug’s starboard engine was disabled, so the master attempted to reverse off the reef with the port engine and rudder. The ATB pivoted, but did not move off the reef, and the tug made contact with the seabed several times. Because of damage to the tug, pollution occurred. The crew were forced to abandon ship and were recovered by local marine authorities.

The tug’s track before hitting the reef.

The tug’s track before hitting the reef.

Investigation findings

Among others, the investigation found that the OOW had likely fallen asleep and missed executing the course alteration point. The OOW’s fatigue stemmed from two sources:

- Acute sleep disruption. He averaged 5.8 hours sleep on the three consecutive days preceding the accident instead of the recommended eight.

- Chronic sleep disruption. He had worked a very challenging and relentless schedule for the last 23 days. This disruption was further compounded by an individual factor: the OOW’s inability to nap on most days during the afternoon or early evening break.

Additionally, as the OOW was alone on the bridge at night without a bridge navigation watchkeeping alarm system (BNWAS) or off-track alarms, there were no mitigating factors to prevent a sleep related occurrence from happening.

Advice from The Nautical Institute

- This is a good example of why it is important to investigate for fatigue in an in-depth and fastidious manner. Even though the OOW may have been compliant with regulatory work-rest requirements, he was suffering from fatigue nonetheless.

- Alone on the bridge at night – not a best practice.

- The use of off-track alarms on ECDIS or ENCs is recommended.

- A BNWAS is another layer of safety that should be considered, even on vessels which are not required to carry this equipment due to their size.

Mars Reports

This accident was covered in the Mars Reports, originally published as Mars 202027, that are part of Report Number 331. A selection of this Report has also been published in SWZ|Maritime’s June 2020 issue. The Nautical Institute compiles these reports to help prevent maritime accidents. That is why they are also published on SWZ|Maritime’s website.

More reports are needed to keep the scheme interesting and informative. All reports are read only by the Mars coordinator and are treated in the strictest confidence. To submit a report, please use the Mars report form.