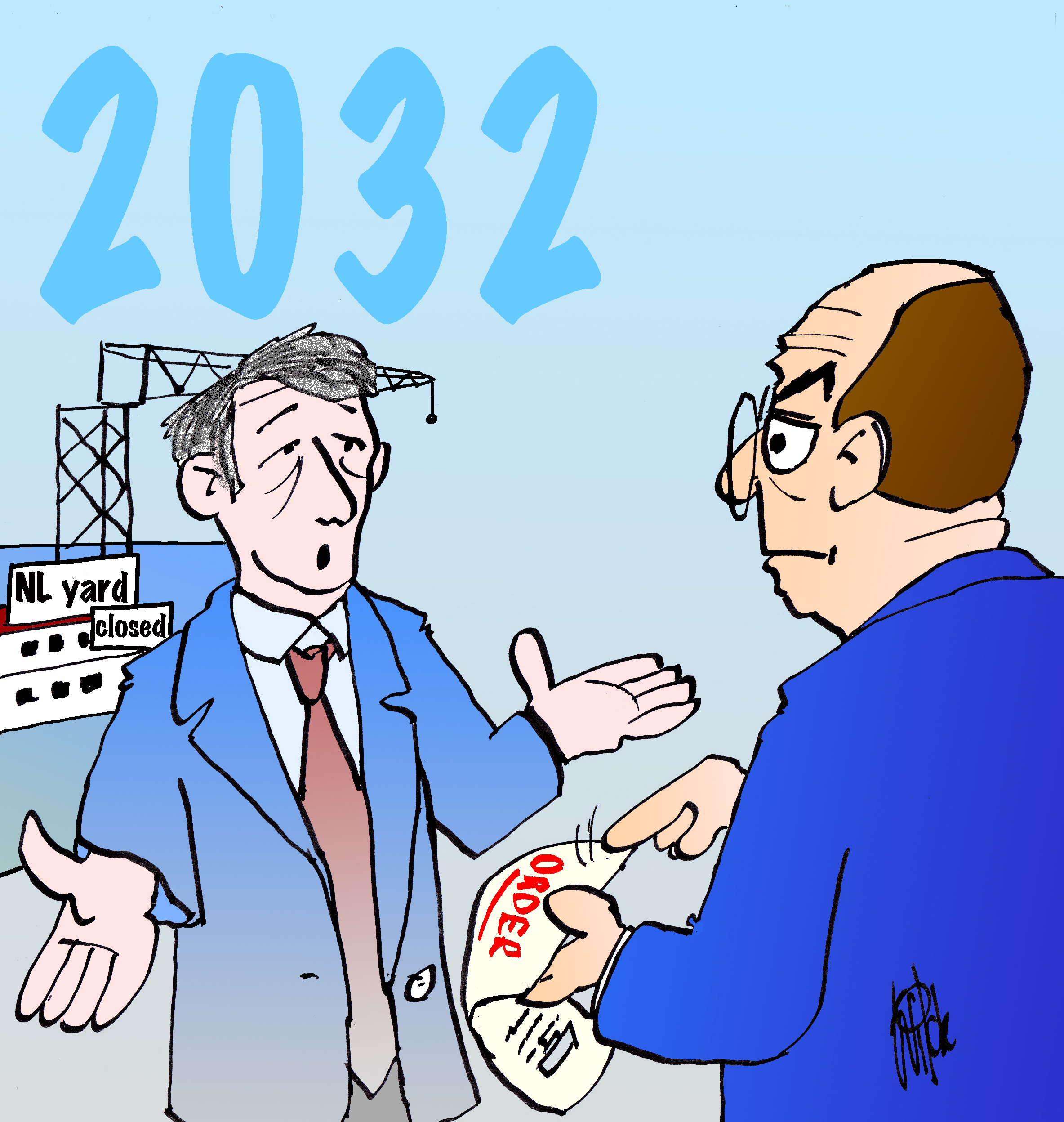

If European politicians and governments don’t act now against the unfair competition of the big Asian shipbuilding nations China and South Korea, there will be just ten years left before shipbuilding in Europe will be gone. And without the ability to build ships, including navy ships, Europe will lose control of supply chains for European industries and consumers and risks very high inflation. We are experiencing a sneak peek of the latter due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the Covid lockdowns that cripple the Chinese industry.

In every issue of SWZ|Maritime, SWZ|Maritime’s editor-in-chief Antoon Oosting writes an opinion piece under the heading “Markets” about the maritime industry or a particular sector within it. In the June 2022 issue, he discusses the VSM’s annual press conference in which the organisation paints a gloomy picture for EU shipbuilding.

The stark warning mentioned above was voiced on 23 May at the press conference of the VSM (Verband für Schiffbau und Meerestechnik e.v., the association of German shipbuilders and maritime suppliers) in which the organisation released the annual figures of the German maritime industry in 2021.

In this press conference, VSM president Harald Fassmer and VSM general manager dr. Reinhard Lüken painted a grim picture of the future of not just the German, but of the whole European shipbuilding industry. The German shipbuilders are struggling with enormous uncertainties in the market. The need for new ships is enormous, but many orders are not granted or go to Asian competitors that are able to offer better financial conditions. ‘Normally we would perish in work, but we are not,’ Fassmer said.

Also read: ‘If suppliers follow shipbuilding, shipbuilding in Europe is finished’

VSM sounds the alarm

Especially the need to produce more energy at sea with offshore wind parks should result in a lot of work for European shipbuilders. Besides the wind turbines, a lot of special ships are needed for transport, crane vessels and cable layers are needed for installation and maintenance has to be carried out with the help of special walk-to-work ships.

The fact is that most of those ships are built in Asia instead of at German or other European yards. According to the VSM, framework conditions are lacking, which could ensure that those massive investments in sustainable energy also enable the own industry to earn money and develop employment and not that, as is often the case, the money flows to Asia. The wind turbines and solar panels now mostly come from China.

To underscore the danger of over-dependence on China, the VSM refers to how dependent Europe and especially Germany have proven to be on the supply of their energy from a bellicose Russia.

‘There is a broad consensus in our society that the use of Russian fuels should be terminated as soon as possible’ and: ‘The maritime industry plays a key role in the search for alternative solutions. The maritime sector connects the German economy with the world, enabling us to diversify our sourcing of energies, essential raw materials, and semi-finished products, and to reduce unhealthy dependencies. The maritime industry is a “freedom industry”’, the VSM says in its press release.

Therefore, the dramatic decline of Europe’s maritime industry should set off alarm bells, the VSM says.

‘The global demand for new ships has doubled, but orders placed in Europe have declined last year by another twenty per cent, even compared to the extremely poor previous year. In 2021, 85 per cent of global orders went to China and Korea. Both nations’ governments have been subsidising their maritime industries massively for years. Even Japan, while maintaining a relatively high domestic demand, barely contributes ten per cent to the global order intake today. Europe’s market share has dropped to less than four per cent. At the same time, many maritime equipment suppliers report growing problems, especially in their business activities in China, a situation also seen in other industries. Problems include local-counter requirements, discrimination, and interference by party officials.’

Shipbuilding capacity is lost

The VSM points out that German shipyards can only accept orders based on fully cost covering prices. They can neither offer government subsidies nor hope for the government to make up for their financial losses. Despite the record demand seen in some market segments, Chinese yards offer shipbuilding prices today that are up to thirty per cent lower than fifteen years ago – although average wages in China have risen by nearly 400 per cent within the same period. Korean shipyards, which have kept up with this price competition, recorded losses of 3.3 billion dollars in 2021.

‘Without a fundamental change in shipbuilding policies, Europe will lose the capability to build seagoing merchant ships on any significant scale over the coming ten years,’ the VSM says.

Right now, Europe’s shipping sector – and the German one disproportionately so – is already highly dependent on Chinese supplies. German shipowners have placed newbuild orders worth 4 billion euros. 55 per cent of them went to China and 44 per cent to Korea, the G20 economy with the highest dependency on Chinese pre-manufactured products. While shipping benefits significantly from state support measures, barely one per cent of newbuilding investments remain within the EU.

China’s influence is growing by the day

China produces 96 per cent of all containers and eighty per cent of all ship-to-shore cranes. China’s enormous influence on global freight transport has become evident in the context of the current disruptions due to Covid induced port lockdowns. At the same time, China continues to expand its influence via favourable financing for newbuilding orders.

The German federal government has become aware of its painful dependence on Russian energy sources and is now taking decisive action to address this issue. The VSM is calling on the federal government to learn from its past mistakes and counteract with the same determination the growing maritime dependence.

The results in EU and German shipbuilding underline the VSM’s worries. While newbuilding orders for China and South Korea soared in 2021 despite last year’s Covid lockdowns, the number of contracts for German and European shipyards shrank. And for this year, too, it just looks very bad with a minimum of orders. German shipyards would like to step into other segments of shipping, but so far, this doesn’t look promising. Just at the beginning of this month, the German shipbuilding industry suffered another setback when the Fosen Yard in Emden had to file for bankruptcy after an investor withdrew an order for six shortsea ships.

Also read: SMM wants to lead transition, but war could cause obstruction

Revenues collapsed

Those statistics about orderbooks and investments mean serious financial consequences for employees and shareholders. Both lose their incomes as workers are made redundant and shareholders get rid of their investments. Data form Clarksons Research show how strong the developments in Europe differ from those in Asia. While the value of orders for European yards shrunk 78 per cent from 22.7 billion dollars in 2019 to 4.9 billion dollars in 2021, the orders for the Chinese grew 110 per cent, from 23 billion dollars in 2019 to 48.3 billion dollars last year.

Furthermore, the South Koreans booked 93 per cent more orders increasing their order book from 22.8 billion dollars in 2019 to 44.1 billion dollars last year and the Japanese after the dip in 2020 recovered in 2021 towards the 2019 level of 9.2 billion dollars.

If one looks back on newbuild deliveries, China’s rise as a shipbuilding superpower becomes even more poignant. The number of deliveries of newbuild ships, expressed in millions of compensated gross tonnage grew a staggering 1064 per cent between 1998 and 2021. The deliveries of the European yards, including Norway and the UK dropped 54 per cent over the same period. The production in German shipbuilding counted in ships went down even faster from 180 in 1980 to less than twenty last year.

This is thanks to the European and especially German shipowners that nowadays order their ships practically exclusively in China and South Korea. Last year, shipowners from the EU ordered 57 per cent in South Korea, 38 per cent in China, four per cent in the rest of the world and just a lousy one per cent in the EU.

Moreover, German shipowners have completely let down the German and European shipbuilders as well. Of their newly built ships, they also ordered just one per cent in the EU.

Naval construction diminished

And it’s not just the European shipowners that let down the European shipyards. The governments have also strongly cut back on naval construction. The association of the German shipbuilders has calculated that German politics has collected a peace dividend of 450 billion euros in defence spending. The number of newbuild naval ships has shrunk to one third of what it was in the eighties (around 200).

‘Our navy sails with fifty-year-old ships,’ Lüken said in the press conference. Last year, it was announced that with 355 ships, the Chinese navy is now bigger than that of the US. Germany now has about 65 commissioned ships.

At this moment, the German maritime industry, especially when compared with its Dutch counterpart, is still significant. Last year, the yards still had a turnover of 18.1 billion euros with 104,400 employees. With 155,100 employees, the German suppliers, important because of for example the engine manufacturers, hit a turnover of 25.1 billion euros. In total, as there is an overlap between these two, this amounts to 200,000 employees and a turnover of a respectable 35 billion.

Right now, the German shipyards have an orderbook worth 15.4 billion euros. Last year, they delivered ships worth 3 billion euros combined and noted newbuild orders of 2.2 billion.

Want to read SWZ|Maritime’s June 2022 issue in full? It is available to our subscribers in our archive. Not yet a subscriber? Become one today!

Also read: ‘Realism must be present in the debate on the energy transition in inland shipping’